Super Bowl 55 feels more like what would happen at the end of an over-the-top dramatic sports movie than reality. There is a global pandemic that has caused millions of deaths, led to severe economic ruin, and paved the way for an unpunished coup attempt on Capitol Hill incited by the outgoing President of the United States. And still, through the rubble, hundreds of millions of pairs of eyes will gaze upon a game with 22 grown men being paid six to eight figure salaries fighting over an oddly-shaped ball for three-plus hours. It’s as if a bomb erupted on the essence of our civil society and, through the fallout, the first thing we turn to in desperate want of normalcy is the specter of Vince Lombardi telling his Green Bay Packers players, “Gentlemen, this is a football.” The second thing we turn to is the birth of Baby Nut.

Reality has provided so much drama that the fantasy escape that football fandom typically provides can’t seem to match it. It’s fitting that this feeling comes when the consensus’ greatest quarterback ever leads his team against a team with a young phenom who may be the one to usurp him some day. Not every Super Bowl has the star-studded cast that this one does, a game featuring the likes of starting quarterbacks Tom Brady (Tampa Bay Buccaneers) and Patrick Mahomes (Kansas City Chiefs). But while the quarterbacks will dominate headlines this week, the real beauty of this game lies in their interaction with the other 21 chess pieces on the field. One can imagine the play-callers staring at a chess board in the upper level of Raymond James Stadium this Sunday, like they’re The Queens Gambit protagonist Beth Harmon on hallucinogens.

At this point, it’s fair to deem Chiefs head coach Andy Reid (victor of last year’s Super Bowl) to be the modern-day Bill Walsh, the widely revered offensive architect whose play-designs rank second to none. Reid’s understanding of football was crafted at BYU in the 1980s when he was a player and graduate assistant. BYU dared to defy the conventional wisdom in centering its offense around… the pass. It turned out that weaving the ball through the air was a more efficient means of moving it than plowing into a wall of 300-pound men three yards at a time. Like it was for BYU, that was the logic with which Walsh and his West Coast offensive scheme created three Super Bowl champion offenses in San Francisco.

Reid, a former Packers assistant to Mike Holmgren who had been Walsh’s offensive coordinator, shared Walsh’s extreme meticulousness in teaching players’ assignments on a screen pass down to the inch. The play-call terminology for both coaches is famously verbose. But all it takes is the naked eye to see that Reid isn’t merely playing the 80s greatest hits on the field. In reaction to his defeat in Super Bowl 39 at the hands of the New England Patriots’ stifling defense, Reid soon allowed his quarterbacks to primarily use the Shotgun alignment to see the field better. It enhanced his already pass-heavy inclinations, but it also opened the door to running the ball, albeit the way college offenses were doing so with new-age option football and jet sweeps. No problem. Reid has long believed the college game was “five years ahead” of the pros. Sure enough, when one watches today’s Chiefs offense overseen by Reid and offensive coordinator Eric Bieniemy, it’s easy to see shades of the Big 12 circa 2015… precisely where Mahomes had been playing then.

On the other side, Buccaneers head coach Bruce Arians has an impressive resume of his own as a quarterback guru. Reid’s oversight of Brett Favre, Donovan McNabb, Michael Vick, Alex Smith, and Mahomes matches Arians’ time with Peyton Manning, Ben Roethlisberger, Andrew Luck, Carson Palmer, and Brady. The most famous phrase attributed to Arians—“No risk it, no biscuit”—similarly shows no sympathy for the tedious prevailing wisdom of past offensive philosophy. Arians comes from the Air Coryell coaching tree—named for Don Coryell and his 1980s Chargers offenses. Air Coryell play-calling is generally less wordy than the West Coast’s, while its routes are more vertical. Arians allows his offensive coordinator, Byron Leftwich, to call plays these days, with substantial input from Brady. But Arians’ fingerprints on this offense are obvious. At 43 years old, Brady’s average depth of target is 9.1, ranking 1st in the league.

Both prolific offenses pose steep challenges for defensive coordinators Steve Spagnuolo (Chiefs) and Todd Bowles (Buccaneers). The tactical choices both men take will have huge importance for this game, and also have little margin for error. The Chiefs are 3-point favorites. There is a path to the Bucs pulling off the upset, but it consists of a combination of self-scouting and recognition of opponent tendencies. The remainder of this post is an amateur guide to doing both from that perspective.

The most effective way to stop Patrick Mahomes is to get him to hand the ball off

Mahomes and the Chiefs offense had sputtered against the 49ers in last year’s Super Bowl until they mounted a furious comeback in the fourth quarter. I believe Reid knew that the 49ers’ formula of light boxes, two-high safeties, and Quarters coverage was likely to resume the following season, similar to how defenses deployed the 6-1 front against the Rams after the Patriots did so in Super Bowl 53. The Chiefs’ reaction this offseason was to make the offense more effective at running the ball against these light boxes. Veteran guard Kelechi Osemele (now on Injured Reserve) was a key free agent acquisition and running back Clyde Edwards-Helaire was the team’s first round pick. But even if defenses are better positioned to stop the pass on early downs, the optimal response isn’t necessarily to run the ball more. This shift in focus may have been a strategic mistake—not a fatal one. Not yet anyway.

The most noticeable time when leaning on the run game hurt the Chiefs was their only loss (excluding Week 17 because starters rested that week): the Week 5 matchup against the Las Vegas Raiders. In that game, the Chiefs ran the ball on 11 of 20 attempts on 1st-and-10 (a down-and-distance when passing is clearly the dominant strategy, based on analytics data). They got away with it in the first half with an unsustainable 100% success rate on 7 rushing attempts. The game was tied 24-24 at halftime. However, the Chiefs’ success rate on their 4 second-half 1st-and-10 rush attempts fell back to earth to 0%. Each of the first three drives in the second half resulted in a punt. All punts were preceded a run play on 1st-and-10. Edwards-Helaire ran for 2 yards, 2 yards, and 0 yards on those three plays. The quick failures of these drives left the offense with lower margin for error in a close game. The Chiefs’ fate was sealed when Mahomes threw an interception on the fourth drive.

The Raiders weren’t selling out to stop the run. They only had six men in the box each of those three plays. Rather, they were getting bang for their buck with each of those six run defenders. Defensive end Clelin Ferrell was the biggest contributor to these stops. As the force defender (whose responsibility is to not let the runner go outside of him), Ferrell thwarted left tackle Eric Fisher’s attempts to reach-block him on two Split Zone plays, with the first one shown above.

On a Counter Trey play, Ferrell recognized that right guard Andrew Wylie was pulling and stunted inside of him by using a wrong-arm move (the defender uses his own outside arm to rip into the puller’s inside armpit). Nose tackle Jonathan Hankins also constricted Edwards-Helaire’s space up the middle. Hankins gave center Austin Reiter fits on the zone plays with a superb bull rush. The Chiefs offensive line isn’t a bunch of world-beating run blockers; the run offense overall rates as 13th in DVOA. They’re a high-variance unit that has their moments.

The Raiders weren’t the only ones to deploy light boxes as a weapon against the Chiefs this year. The Bills did so the following week to an even more drastic degree; according to PFF, they averaged just 5.64 men in the box on all downs and 5.86 on early downs that night. The Chiefs ran the ball on a season-high 22 of 32 1st-and-10s in that game. 31 of their total rushing attempts were against five or six man boxes, and none were against eight man boxes.

The Chiefs have answers for when you’re trying to bait them into running

The problem for the Bills is that their run defense graded poorly that game. No Bills defender earned a run grade higher than 65.0 for PFF and defensive tackle Ed Oliver had an abysmal 28.8 run-defense grade. The grade matches the eye test, as Oliver got driven off the line of scrimmage multiple times, including a 9 yard gain on a Split Zone which was the Chiefs’ first play from scrimmage.

In that game, the Chiefs thrived on a combination of abnormally superb run-blocking and play-design. Fisher—who got injured in the AFC Championship Game and won’t play Sunday—was especially dominant executing a rip-and-run technique (trying to reach a defender before driving him to the sideline) on zone run schemes versus defensive end Mario Addison. One such play illustrating Fisher’s dominance was a Zone Lead from a two-back formation in Shotgun, with Travis Kelce lead-blocking through the B-gap for Edwards-Helaire on a 14 yard gain.

Earlier in the game, Reid set up the longest rush of the day by putting Tyreek Hill in orbit motion toward the backside of a Split Zone. Kelce pulling to the same side as Hill froze the backside defenders, while Edwards-Helaire easily outmaneuvered the safety who was responsible for the playside C-gap. The Chiefs were much more efficient on the ground than the previous week, as they earned a staggering 77% success rate on 1st-and-10 rushes en route to a narrow 26-17 victory.

“I think you got to look at this is an explosive offense mainly through the air, so you got to pick your poison here,” Buffalo head coach Sean McDermott told reporters after that game. “What you’re trying to take away, and then on the other end, you’re going to give a little bit. And so I’m not saying that we liked what we gave up in the run game. That said, towards the end of the game, we were in the game as opposed to some people are getting blown out because the ball is flying over their head.”

McDermott has a point. His offense earned just 206 yards the entire game and the Bills still only lost by 9 points. The Chiefs rank 13th in rushing DVOA and 2nd in passing DVOA, and they got to play an offense that was more like the 13th-most productive in the NFL than one of the two best. With even just average-quality run defense (or offense), the Bills plausibly win. So the formula seems cut and dry, right? Bait the Chiefs into running the ball on early downs, have your front four execute, force a few extra punts in the game in the process, and you have a shot?

There is one glaring limitation to leaning on this plan too much: Andy Reid is a smart coach. He watched the tape of the games against the Raiders and Bills. He then had a better game-plan in rematches against both teams. In their Week 11 victory over the Raiders, the Chiefs passed on 21 out of 32 1st-and-10 and earned a 67% success rate on those passing plays. In the AFC Championship Game against the Bills, the Chiefs passed on 17 out of 27 1st-and-10s for a 65% success rate on passing 1st-and-10s, and the game was out of reach much faster.

On a 1st-and-10 in the Red Zone, the Bills showed two-high safeties with just five box defenders. Reid understood throughout both rematches that when the defense is inviting you to run the ball on early downs, there is a good reason. Rather than simply running the ball against a light box here, the Chiefs sent Kelce in short motion to show Mahomes the coverage he would pass against. This showed that the Bills were in zone. The deep off alignment of the cornerbacks also tipped that it would be Cover 4. Mahomes knew that the swing route by Edwards-Helaire would stretch the flat defender, leaving a clear throwing lane to connect with Hill who broke on his curl route beneath the deep zones. The static alignment of the defense made it easier for the Chiefs to stick with the dominant strategy of passing. Opposing defenses must respond with curveballs of their own.

The Bucs are the best run defense in the NFL by a wide margin. That’s both a blessing and a curse

Todd Bowles’ Tampa Bay Buccaneers defense is much different stylistically than any other defense. For starters, they’re the best run defense in the entire NFL by a wide margin. This was in spite of the injury absence of stellar nose tackle Vita Vea who finally returned in the NFC Championship Game. Vea, Ndamukong Suh, William Gholston, Jason Pierre-Paul, and Shaquil Barret collectively form one of the best groups of run-stuffers in years. The Bucs’ defensive line is more than capable of holding their own in the trenches without extra men in the box. This is especially true now that the Chiefs’ offensive line is expected to be without both Fisher and Mitchell Schwartz at offensive tackle.

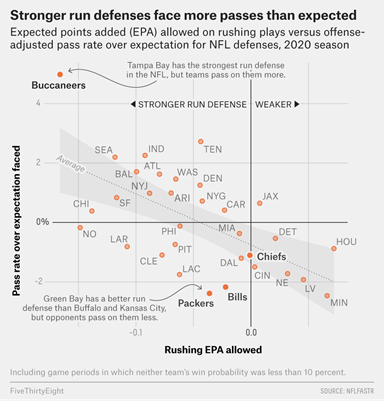

There is a not-so-obvious disadvantage to the Bucs that comes with opposing offenses’ widespread fear of running the ball on them. FiveThirtyEight contributor Namita Nandakumar showed that the Bucs face significantly more passes than expected when controlling for down, distance, scoreline, opponent tendencies, and other factors. It’s widely known that the Bucs are good at stuffing the run, so teams pass the ball more to avoid that gauntlet. The problem for Tampa Bay, as we’ve discussed, is that passing the ball on early downs is more efficient than rushing.

Making matters worse, Bowles has a clear tendency to stack the box (all else equal) relative to the rest of the league. According to FiveThirtyEight contributor Josh Hermsmeyer, he has the third-highest Defenders in the Box Over Expected (DBOE) average of +0.29 (interestingly, Chiefs defensive coordinator Steve Spagnuolo ranks just behind him at fourth with a DBOE average of +0.24). That should be to the Bucs’ detriment against a passing offense as prolific as the Chiefs. New Jets head coach (and former 49ers defensive coordinator) Robert Saleh is in the same ballpark as Bowles with a DBOE of +0.23, but he was willing to break tendency in last year’s Super Bowl.

That was not the approach that Bowles took in the Bucs’ regular season matchup in Week 12 against the Chiefs. The Chiefs passed on 18 of 29 1st-and-10s in that game. This was their third-most pass-happy rate on first down in the entire season. The Bucs’ problems were apparent on the first play from scrimmage—a 34 yard pass. Reid designed an RPO which packaged a Split Zone run with a curl route by Demarcus Robinson and a wheel route by Hill off jet motion. Kelce pulling across the formation lured Barrett to execute the same kind of wrong-arm move Ferrell did, leaving overhang defender Antoine Winfield Jr. responsible for the run outside the tackle box. The Bucs instinctively assume gap control against run concepts, with seven defenders now playing the run. Advantage Chiefs.

It was clear to Mahomes that the Bucs were playing zone because no one shadowed Hill across the formation. The curl route by Robinson would have been the primary read against Cover 3 (the likely coverage with one-high safety before the snap), but the Bucs rotated to Cover 2 instead. The curl route occupied safety Jordan Whitehead because Winfield got lured in to play the run and couldn’t be two places at once. Cornerback Sean Murphy-Bunting executes his assignment of covering the flats, but this means no one is covering Hill.

The Chiefs went to the RPO well again to attack Cover 3 in the first quarter by packaging All Slants on the trips side with an Inside Zone in the opposite side. Mahomes read linebacker Devin White who had been cheating toward the run, vacating space for Hill behind him to pick up 19 yards. This is another sequence that perfectly captures how an offense can use the defense’s instinct to fixate on gap control against itself.

The Chiefs’ longest play of the day again was the product of the Bucs’ defense being dialed in to run tendencies. For years, Shotgun-based offenses tended to align the running back on the same side as the tight end to set up zone-blocking runs away from the tight end. The Chiefs’ tackles also had been in two point stances, another common tip-off to a run. The Outside Zone play-fake here and the Bucs’ slant stunt towards the “play-side” leaves Mahomes with a wide throwing lane through the right B-gap. The unsung hero is right tackle Mike Remmers who executes a great angle set (45 degree step and punch) on Pierre-Paul. Pierre-Paul had been squeezing down on Remmers as if he had to play contain on the cutback lane.

To attack the back end, the Chiefs again use pre-snap movement with Kelce shifting from the wide receiver position next to Hill to become the wide receiver on the opposite side of the formation. Again, the Bucs are in one-high and don’t shadow Hill, signaling to Mahomes that it’s Cover 3. The formation before the shift would have matched cornerback Carlton Davis with Kelce on vertical routes, while Whitehead and Winfield could bracket Hill out of the slot on his vertical routes. Instead, Winfield is relegated to eyeing second tight end Nick Keizer. Whitehead moves from the left hashmark to the right hashmark toward Kelce, leaving him powerless to help Davis against Hill. Hill executes a smooth out-and-up route that lets him blow past Davis for a touchdown before he knows what’s happening.

The run game clash on 3rd-and-short is brains versus brawn

The Bucs’ tendency to go all-in against the run may be a liability on early downs, but it is advantageous for them in situations when the offense’s dominant strategy is to run like 3rd-and-short and 4th-and-short. These are down-and-distances when the league-wide success rate is 68% on run plays and 56% for pass plays. Only the Ravens faced a lower percentage of run plays in these situations this season than the Bucs. The Bucs also allowed the league’s lowest success rate (50%) on rushing attempts in these downs. The Chiefs tend to be one of the run-heaviest offenses on 3rd-and-short and 4th-and-short; they ranked sixth with a 61% rushing frequency. In the Week 12 matchup, the Chiefs attempted 3 runs on these downs with just one success. This was the one advantage the Bucs exploited.

On a 3rd-and-1, the Chiefs attempted a Power O run to the D gap from an Offset I formation. The Bucs took away the path of least resistance up the middle by clogging the A and B gaps with a Bear front. The slant by Whitehead into D-gap occupies Kelce, while the penetration in the B-gap by defensive tackle Steve McLendon prevents left guard Nick Allegretti from kicking out the end man on the line of scrimmage. That would be Lavonte David who flows to the C-gap unobstructed. Another reason David makes the tackle with ease is because White holds up fullback Anthony Sherman at the point of attack. This leaves Edwards-Helaire with no room to run.

The Chiefs’ most creative run plays tend to be in the low red zone (<= 10 yards to goal), another situation where running the ball is the most successful strategy league-wide (rushing success rate is 56% and passing success rate is 45%). And while the Chiefs had the third-highest passing rate in the low red zone (60%), they also had equal success rates here on the ground and in the air (54%). The Chiefs’ plan against the Browns in the AFC Divisional Round for low red zone runs may be a blueprint for how they can overcome the Bucs’ stout front. Their answer was to use a running game without the running back being the focal point in these high-leverage situations. Brains versus brawn.

On a 3rd-and-2, the alignment of Hill in the backfield and use of Mecole Hardman on jet motion stressed the defense in both directions. Hardman (0.625 EPA, 50% SR, 6 rushes) and Hill (0.504 EPA, 62.5% SR, 16 rushes) are both efficient on run plays, so the defense can’t just key on either. The horizontal stress Hardman provides away from the play-side makes it easier for the line to back-block their Power O assignments. (In the AFC Championship Game, the Bills found out the hard way that Hardman is capable of 50 yard gains on the jet sweep).

This time, Allegretti isn’t kicking out the end-man-on-the-line-of-scrimmage, Myles Garrett. He’s climbing up to the second level instead. Mahomes is reading Garrett to determine whether to hand the ball to Hill or deliver a shovel pass to Kelce. It’s like a read option play but one that doesn’t involve a quarterback keep. This Power Read Shovel, or Power Shovel Option, play became one of Reid’s red-zone staples in 2017 after he stole it from then-University of Pittsburgh offensive coordinator Matt Canada (who now holds the same position with the Pittsburgh Steelers). It’s a novel way to get the advantageous angles from gap-blocking without having to actually block a game-wrecking defensive lineman.

Play-designs that include quarterback keeps were also used in these situations. The Chiefs scored a touchdown against the Browns on the goal line from a speed option in which Mahomes ran the ball into the endzone. They already had similar success with a speed option on a 3rd-and-1 against the Bucs—this play was their one success on the ground in 3rd-and-short.

This under center version of the speed option is a throwback to Tom Osborne’s Nebraska I-Option offenses. It’s a testament to Reid’s football mind that he can seamlessly integrate a classic from decades ago into his uber-modern offense. The offset I formation messes with the Bucs’ keys, as they align in a similar Bear front on the earlier failed Power O run. The Chiefs use White’s aggressiveness against him as Keizer just has to provide a small shove to open up a lane for Mahomes to pick up 17 yards. The point in showing this is to say that, while the Bucs run defense is stout, Reid has answers for it. Tampa Bay must be willing to pivot from its run game tendencies because Kansas City will certainly pivot from theirs.

The Bucs’ tendency to blitz can work to their advantage… if they break that tendency

There is one other tendency the Bucs defense must be willing to pivot from in the Super Bowl. The Bucs ranked fifth in blitz percentage this season, sending 5 or more rushers after the quarterback on 39.0% of snaps. This tactic usually worked to their advantage even against elite quarterbacks. For example, in Week 6, Aaron Rodgers completed just 3 of 12 passes for 28 yards, two interceptions, and three sacks on blitzes. But there is little reason to believe this success can be replicated against Mahomes. This season, Mahomes has an average of 0.54 EPA/play against the blitz (1st), compared to 0.22 EPA/play (9th) without the blitz. He goes from above-average starter to the Incredible Hulk against the blitz.

In the regular season matchup against the Chiefs, Bowles found this out the hard way. On a 3rd-and-8, the Bucs showed a two-high look before the snap. The play-call was for a five-man blitz with Cover 1 behind it. The pre-snap appearance of a two-high shell actually left the Bucs more vulnerable to the Chiefs’ Three Verticals play-call. Hill aligned as the no. 3 receiver against Davis, while Mike Edwards aligned just to Hill’s right on the hashmark. Hill immediately beat Davis to gain inside leverage and Edwards had no angle to provide help. Without the safety rotation, Edwards likely would have been aligned between the hashmarks and had more time to react. David had successfully executed a pick on a cross blitz that took Wylie out of position to pick up White; if not for Hill’s immediate release, the call may have succeeded. Instead, it’s a 44 yard touchdown.

Later in the game, the Bucs attempted to blitz David through the A-gap in the Red Zone later in the game, only for Reiter to pick him up. Mahomes had been operating from an empty set and the blitz was paired with Cover 1. The high safety was out of position to assist with Hill because the empty set stretched the defense thin. Hill again beat Davis to the outside with a free release to secure his third touchdown catch of the day.

There are some positive takeaways for the Bucs from the game too. I don’t think it’s coincidence that both of the Bucs’ two sacks against Mahomes came on four-man rushes. The second one was Bowles’ best play-call of the day, in my opinion. It came on a 2nd-and-6 in the fourth quarter in which Kelce was isolated in the boundary and Hill aligned as the no. 3 receiver in a trips set to the right.

The Bucs show two-high safeties before the snap and the body position of the cornerbacks (facing Mahomes) signal zone. Mahomes is likely expecting Cover 2. The two-man route combination between Hill and Mecole Hardman (the no. 2 receiver) is called Dagger; Hill runs a vertical route targeted at the hole between the two safeties, while Hardman runs a dig route between the underneath and deep zones. Kelce’s presence on the opposite side occupies one safety, Whitehead. The additional vertical route by Robinson (the no. 1 receiver) would occupy the other safety, Winfield, and give Hill a huge lane if this was Cover 2.

But it isn’t Cover 2. Instead, Bowles called Cover 6 (also known as Quarter-Quarter-Half) which is a hybrid coverage featuring Cover 2 rules on one half of the field and Cover 4 on the other. This is a great coverage to account for 3×1 sets with two potent receivers—one who excels at isolation routes like Kelce and another who can stretch the field like Hill. The Cover 2 rules on the isolation side allow Murphy-Bunting to focus on short routes like the quick out Kelce runs. The Cover 4 rules on the trips side task Davis with carrying Hardman on the vertical route, freeing Winfield up to close in on Hill. Whitehead is already in good position to attack Hill at the catch point because he’s on the opposite hashmark.

The back seven’s victory stressed the offensive line which was losing the battle in the trenches. The Chiefs accounted for threat of White potentially blitzing the left A-gap with a half-slide pass protection; everyone except Remmers protected the gap to their left. Reiter’s eyes go to White immediately, leaving him unable to assist Wylie with Suh right away. Suh appears to have a gap-and-a-half assignment, meaning he primarily attacks one gap and switches to another if his keys dictate he should. This is contrary to Bowles’ usual inclination to be gapped out, assigning every gap to one specific defender.

Suh’s assignment frees David to drop into his zone immediately without worrying about a run fit; this allows David to take away Hardman’s dig route in Mahomes’ progression. Barrett pushing Remmers into the pocket with his own bull rush means Suh can close off Mahomes’ throwing lane to the trips side. Suh does this by flowing out of the A-gap and into the B-gap. On the other side of the box, the Bucs use a T-E stunt in which Khalil Davis exchanges gaps with Pierre-Paul who ultimately gets the sack; Davis uses a great rip move which makes Mahomes now unable to flee the pocket in either direction. It’s not a typical play-design for the Bucs, but the fact that it’s in their arsenal hints at a path to victory.

Why sim pressures may be the Bucs’ best way to pressure Mahomes

Sim pressures may be a useful tactic for the Bucs to replicate this play against the Chiefs. Sim pressures occur when the defense shows an intent to blitz 5 or 6 before the snap, only to bring a 4 man rush instead. The illusion of a blitz can create favorable one-on-ones for the defensive line, as offensive linemen hesitate to provide help. This is crucial because those matchups are where the Bucs have a decisive advantage, and sim pressures are a way of achieving that advantage without the risks of blitzing Mahomes. The Bucs have a built-in edge in using sim pressures because they blitz so often that the threat is credible.

The Falcons held the Chiefs to 17 points this year, and sim pressures were a key part of their performance. On this 2nd-and-7, they begin with a Mug front (a linebacker in each A-gap) which threatens the double A-gap blitz. The advantage of the Mug front is that it limits the pass protection options for the offense. To oversimplify enormously, the most common pass protections are full-slide (the entire line steps one direction, with the back accounting for the backside edge), big-on-big (the center and running back pick up the linebackers, and the rest of the line handles the front four), and half-slide (most of the line steps one direction, but the remainder steps the other).

Half-slide protections work best if the slide is away from a B or C-gap occupied by a linebacker. This is because the quarterback is now responsible for that gap. When both linebackers are in the A-gap, it’s suicidal to leave the quarterback vulnerable to the blitz on his own. The defense can reasonably expect the offense is choosing between two kinds of protections, not three.

The Chiefs chose big-on-big. The Falcons not only drop both linebackers, but also drop defensive tackle Jacob Tuioti-Mariner into coverage too. This leaves Wylie and Reiter both punching air after the snap. The plot twist is that the Falcons show a three-man rush first, but it’s really a delayed four-man rush. Nickel corner Isaiah Oliver has a free shot through the B-gap because Fisher is blocking Dante Fowler and Allegretti has been assigned Grady Jarrett. Even though the Chiefs have five blockers (with running back Darrel Williams releasing into a route when he sees the linebackers drop), the four-man rush works because two of the Chiefs’ blockers are out of position to stop the pressure.

A key to pressuring Mahomes is to have the right coverage on his electric weapons. This is no small feat when the Chiefs use a trips set with both Kelce and Hill on the same side, as they did here. The coverage is Tampa 2, a rare coverage in the modern NFL but one that was all the rage in the late 90s-early 00s. The rules are just like Cover 2 with two safeties dropping into a deep zone, but with the wrinkle of a middle linebacker also releasing into the hole between them. That Deion Jones executed this drop from the line of scrimmage shows what a freak he is. This is why the seam route by Kelce got shut down. Jones dropping deep allows the deep-half safety to just worry about Hill who broke his route short on a comeback here. White’s 4.42 40 time has a comparable to Jones’ 4.38. The Bucs are one of the few teams that can plausibly copy this play-design.

The Raiders again showed a good blueprint for the Bucs to follow in their use of a sim pressure. Theirs simply was a three-man rush that looked like a four-man rush. On a 3rd-and-9, the Raiders used a three-man front with Arden Key aligned as a “Joker” linebacker. Key acted as if he was blitzing the A-gap and this occupies Wylie’s attention. Schwartz (now on Injured Reserve) is certainly capable of handling a one-on-one. But the problem with leaving him on an island emerges when Ferrell successfully spins into the backfield past Fisher. Mahomes flees to the right side where Schwartz had redirected Maxx Crosby. If Wylie had been helping Schwartz, he could have picked up Crosby before Mahomes got sacked from behind.

Hill was absent in this game, but the coverage the Raiders used is a good one to contain him when he and Kelce are on opposite sides of trips sets. The coverage appears to be a variation of Cover 7 which is a complex set of rules developed by Alabama head coach Nick Saban which are specifically designed for trips sets. The coverage on the trips side is called the Box coverage (there are 4 defenders), while the coverage on the other side is called the Triangle coverage (there are 3 defenders). There are nearly endless ways to account for route combinations to either side. I won’t attempt to guess the Raiders’ exact rules, but the presence of a deep safety on Kelce’s side signals that they were prepared to effectively bracket him. The trips-side cornerback dropping deep in reaction to the in-breaking route by Robinson signals that the Raiders also were prepared to bracket Hardman (the Hill proxy, if you will) who is running a deep over route.

If executed well, Cover 7 allows two extraordinary weapons to get neutralized in ways that aren’t obvious to the quarterback just by looking at the defense before the snap. It’s particularly advantageous on 3rd-and-long because the defense does not honor the threat of the run game, so the pass rush can pin its ears back. The quarterback meanwhile must recognize and react to a coverage which is more complex than spot-drop zone or pure man. One more thing: the Chiefs offense found itself in this dilemma in the first place because they insisted on running the damn ball on 1st down!

To read the Super Bowl 55 Preview, Part II, click here