The Moneyball principle for Major League Baseball is that, while using statistical analysis, small-market teams can compete by buying assets that are undervalued by other teams and selling ones that are overvalued. The more competitive salary cap-driven market structure of the NFL still means the Moneyball principle is important. In a league where each team has the same amount of financial resources, the teams that are the best at valuation are even more likely to be the most dominant. The ultimate challenge is to identify who these undervalued football players are, and that’s what this post will do.

I quibble that the book and film Moneyball glosses over the role of superstar players like Mark Mulder, Tim Hudson, Barry Zito, and Miguel Tejada. But the basic point that the Oakland A’s were rewarded at the margins for finding undervalued players like Scott Hatteberg, David Justice, and Chad Bradford is true. Baseball analytics godfather Bill James had long theorized (among many other ideas) that MLB franchises had undervalued batters’ ability to get on base via walks. “He gets on base” became a mantra for general manager Billy Beane, when explaining why he was interested in acquiring a player who turned off his more traditional scouts.

The evolution of analytics in football is more recent. It’s fundamentally true that baseball is a sport for which it is easier to quantify individual player value. The sport is somewhat like a series of one-on-one matchups between the pitcher and the hitter. But those of us who observe football at a more complex level aren’t exactly cavemen either. We have found some basic strategic insights: (a) offensive performance is more stable from year-to-year than defensive performance, (b) passing is more efficient than running in most—but not all—down-and-distances, and (c) passing offense is more stable from year-to-year than rushing offense. Those insights make for an excellent starting point, but we can identify narrower opportunities for teams to acquire value.

Play-Action Efficiency: The football version of “He gets on base”

If there was a football equivalent of team on-base percentage, it would be team play-action percentage. The play-action pass is a passing play that first shows the disguise of a run play with a fake handoff. We know play-action is essentially an easy button for generating additional efficiency through the air. According to Andrew Rogan, “the average play action play over the past four seasons (2017-2020) has averaged over .1 EPA per play, compared to about .05 for passes not using play action, and -.08 for runs.” FiveThirtyEight contributor Josh Hermsmeyer also found that there are no diminishing returns to play-action with additional usage.

The remarkable efficiency of play-action makes it the logical piece of a team’s offense to emphasize. If there is a way to make play-action more effective, teams should pursue it. The conventional wisdom which still persists today at the highest levels of football has long been that offenses must “establish the run” to make play-action effective. This was the philosophy behind the Single-Wing, Double-Wing, T Formation, Wishbone, Wing-T, Split Back Veer, I-Option, and many other old-school offenses. That philosophy feels intuitive. It’s understandable to think selling a fake handoff will be easier if your offense runs the ball often and well.

Counter-intuitively, analytics expert Ben Baldwin disputed that cause-and-effect linkage. He found that play-action passing performance was independent of both rushing volume and rushing performance. Almost none of the variation in play-action yards per play across six seasons was explained by total rushes, rush percent, or rushing success rate (that’s what R2 represents). Play-action seemed to work well independently of anything involving the run game. The old-school thought that teams must “run to set up the pass” seemed to be an old wives’ tale.

That is, until Rogan found a somewhat different result. Rogan thought that omitted variable bias was driving Baldwin’s finding. The basic point he made was that there are distinct characteristics of a play-action pass that can generate additional efficiency on their own, independent of the play-fake per se. These include designed rollouts, longer time to throw, and crossing routes. At a conceptual level, Rogan’s hypothesis is this:

So that whole process laid out above about how play action fools linebackers? It doesn’t apply to defensive backs. DBs really just make the same reads regardless of whether it’s a run or pass. There just is no real chance for a corner to get fooled off the play fake, and safeties are immune for the most past as well (again this is a little simplified, but let’s not dive too deep into the chalk).

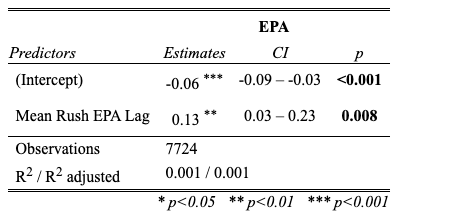

To back this hypothesis up, Rogan then creates a regression model for expected points added (EPA) on play-action pass attempts. He uses “a variable called ‘Mean Rush EPA Lag’ which is just the cumulative mean of rush EPA for a team up to that point in a game” on plays with minimum 8 rush attempts and maximum 35. The crucial observation Rogan makes is that, on short throws (less than 10 air yards), Mean Rush EPA Lag is a statistically significant predictor of play-action passing EPA, based on the low p-value. These short throws are the ones with routes occupying the space abandoned by linebackers who flow to their run fits.

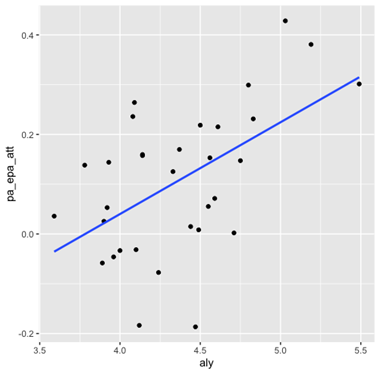

This pattern is not found in either Medium Throws (10-25 air yards) or Deep Throws (more than 25 air yards). That discrepancy supports Rogan’s explanation of play-action. The high efficiency from deep play-action throws then is driven by the depth of target, not the play-action per se. Play-action does have an impact on linebackers who must respond to run fits, but not on defensive backs who don’t have to. Below is the bivariate regression for Deep Throws that Rogan shared which shows the high p-value for Mean Rush EPA Lag.

Play-action efficiency then appears to be independent of the run game in Baldwin’s research because deep and medium throws obscure the dependency found in short throws. Deep and medium passes—especially those using a crossing route or a rollout—work well in general, whether they are packaged with play-action or not. One implication is that the NFL’s slow but steady evolution toward emphasizing the passing game is correct. Quarterbacks, offensive tackles, edge rushers, receivers, and cornerbacks consistently dominate salary cap space and the top 10 draft selections. It’s easy to take for granted in the modern era, but this really is progress from the “three yards and a cloud of dust” mindset.

The other implication is there is an opportunity to identify undervalued markets of players who create passing efficiency on offense and take it away on defense. In my opinion, Rogan’s findings hint at what types of players are undervalued. I find his analysis to be a compelling reason to believe that the run game affects how well a team executes play-action on shorter targets. Seam routes, shallow digs, and shallow crossers all give the quarterback a high-percentage throw in the space vacated by linebackers entering their run fit. It seems correct that running the ball frequently is inefficient, but running the ball well still has beneficial ripple effects which could be large; the same likely goes for defense, as defending the run well has similar ripple effects. Players who are effective in the run game likely add value to the passing game in ways that existing analytics research hasn’t captured.

The Moneyball Offensive Linemen

There is evidence backing a relationship between an offense’s run-blocking ability and play-action passing efficiency. It began to be uncovered when ESPN contributor Mina Kimes observed that, for the 2018 season, each of the top four teams (Patriots, Chargers, Rams, Saints) in offensive DVOA on play-action passes all ranked in the top five for adjusted line yards. Then, USA Today contributor Steven Ruiz found that the R-squared between Football Outsiders’ Adjusted Line Yards and Play-Action Pass Average EPA for that season is 0.25.

Similarly, Ruiz found that the R-Squared between the latter and PFF’s run-blocking grades was 0.23.

What should be the takeaway from this? Mine is that there is more hidden value in the ability to run the football than analytics minds had previously thought. Rogan spoke of how linebackers simply can’t delay entering their run fits; typically, a run play will either be stuffed immediately or not at all. But what does a defense do if their front defenders enter the fits immediately and still yield 4+ yards per rush to the likes of the 2018 Rams? The counter is (with rare exception) to add more defenders to the front. Defensive play-callers are so averse to allowing long methodical drives that they leave the back end of the defense under-manned.

This brings me back to answering to the original question of this post. Offensive linemen who excel at run-blocking (even if they aren’t excellent pass-blockers) may be undervalued across the league. The league has typically paid a premium to acquire elite pass-blockers instead, while numerous quantitative studies show that sacks allowed are primarily a quarterback statistic. The valuation of offensive linemen is likely too heavily determined by the passing game which they have less influence over. There is no question that using resources to maximizes the passing game offers the highest returns, and this thesis fits perfectly in that school of thought. There is a positive externality to the effectiveness of passing in acquiring linemen who excel on run plays.

My nominee for the Moneyball Offensive Lineman is Patriots tackle/guard Michael Onwenu, a sixth round pick in last year’s draft who started primarily at right tackle last season. He was the 123rd-highest paid tackle, rating as the sixth-best run blocker and ninth-best blocker overall on PFF. There are other outstanding values among the offensive linemen too. My honorable mentions would be Vikings tackle Brian O’Neill (58th-highest paid tackle, 10th-best run-blocker, 24th-best overall on PFF), 49ers tackle Mike McGlinchey (30th-highest paid tackle, 2nd-best run-blocker, 19th-best overall on PFF), and Browns guard Wyatt Teller (37th-highest paid guard, 1st-best run-blocker).

I don’t think it’s a coincidence that all four of these players come from teams that use play-action at a high rate. Passes off Power O play-fakes have long been the Patriots’ tactic of choice to lure linebackers away from throwing lanes. Throughout the Brady years and continuing last season, the Patriots ranked near the top of the NFL in play-action percentage. An example last year against the Seahawks showed the impact of Onwenu specifically. At right tackle, Onwenu uses his absurd body strength and deceiving footwork to sell the run fake. All-Pro linebacker Bobby Wagner freezes in anticipation of the run lane emerging in the C-gap behind Onwenu. Instead, Newton gets an open seam to connect with Julian Edelman for a 16 yard gain.

Concerns about Onwenu’s weight and pass protection technique were the main reasons why he fell to the sixth round. That overshadowed the value he unquestionably provided as a superb run-blocking prospect. Front offices failed to see Onwenu wasn’t merely allowing them to run for “three yards and a cloud of dust” on loop. The seams which open just outside the tackle box are thanks to the fear in linebackers’ eyes as they anticipate this mountain of a man firing at them out of his stance.

The Moneyball Defensive Linemen

I won’t tackle the question of whether defensive play-callers are irrational in how much they fear the run game (there are plenty of others suggesting the majority are). Instead, I’ll promote a compromise that addresses the need to stop the run, but not at the cost of letting offenses dominate in the passing game. Like their run-blocking counterparts on offense, defensive linemen who excel against the run offer more value than conventional wisdom suggests. PFF data scientist Eric Eager found a negative correlation between number of box defenders and run-defense grade for interior linemen.

Eager also showed that lighter box counts correlate with lower EPA allowed. Run-defense grade is a stable measure at the individual player level, so there appears to be real value here.

My interpretation is Eager’s findings show the same pattern that Ruiz illustrated, but from the defensive point-of-view. Defensive lines that can shut down the run without much help from linebackers or defensive backs offer hidden value in the passing game as well. Coverage grade also appears to be a better predictor of sacks than pass-rush grades, hinting that pass-rush grades are generally over-valued. Joey Bosa may be worth every penny, but teams are also paying Frank Clark and Trey Flowers 80-90% of what Bosa makes. The dilemma is that there are only so many defensive linemen who consistently disrupt the quarterback. That makes the ones who do super valuable, but it also inflates the valuation of the next tier. This is all the more reason to look for value where the league doesn’t see it.

My compromise on defensive roster-building philosophy is this: by all means, prioritize stopping the run. But do so with quality, not quantity. Get the most bang for your buck with light boxes and ensure the players who are in the box are excellent at stopping the run. You may be wondering whether I, as an Eagles fan, am taking a shot at former defensive coordinator Jim Schwartz whose philosophy was essentially “acquire lots of great run defenders and then add more defenders to the box anyway.” You may also be wondering whether I am skeptical of how Schwartz gave defensive ends no contain responsibilities, as Chris Long revealed, and forced nickel cornerbacks and box safeties into the run fit instead. Well, I would be lying if I said my fan experience had no influence over coming to these conclusions.

My nominee for Moneyball is new Cowboys’ defensive tackle/end Brent Urbanwho became the 133rd-highest paid defensive end this offseason. With the Bears last season, Urban ranked as the 3rd-best interior lineman on run defense and 22nd-best overall. My honorable mentions are Folorunso Fatukasi (100th-highest paid defensive tackle, 2nd-best on run defense, 14th-best overall), Ravens’ Derek Wolfe (42nd-highest paid defensive end, 5th-best on run defense, 50th-best overall), Chiefs’ Derrick Nnadi (71st-highest paid defensive tackle, 7th-best on run defense, 26th-best overall).

A great example of Urban’s unsung value came from this interception off a play-action screen against the Detroit Lions. The Bears are in an odd front with three linemen including Urban all aligned head-up on the offensive line. All three are two-gapping, meaning that they can penetrate the gap to either side. Specifically, they will enter the gap to the side of the run action. In an odd front with two linebackers, the weak-side linebacker lags in the A-gap opposite of the nose tackle. Meanwhile, strong-side linebacker Danny Trevathan is free to drop into coverage because he is not part of the run fit. Urban’s two-gap assignment basically frees him up to avoid conflict.

Urban doesn’t do anything flashy here, just his job. He’s applying a bull-rush on left tackle Taylor Decker to make sure Matthew Stafford has no escape route. This tactic forces Stafford to speed up his decision when he faces an unblocked Robert Quinn charging at him. Fellow 3-4 end Bilal Nichols makes a fantastic play of his own by recognizing the screen immediately and gaining the interception.

The thing I want to highlight most about this play is how the Bears defense had answers for everything. The three down linemen and a weakside linebacker clogged the interior gaps by themselves. There were cover men deep and shallow alike. Players like Michael Onwenu and Brent Urban might not show up on SportsCenter’s top ten, but they facilitate these kinds of plays all the same.