To read the Super Bowl 55 Preview, Part I, click here

The Super Bowl is being framed as “Tom Brady versus Patrick Mahomes” which seems odd because those two players will never line up on the field at the same time. It’s not like an NBA Finals game when LeBron James and Steph Curry will be on the court together the vast majority of the game, or a World Series matchup which consists of a series of one-on-ones between the pitcher and batter. And yet, most important consideration for the Bucs offense may indeed be the Chiefs offensive players who they won’t physically line up against.

The clock will not beat Patrick Mahomes. The Bucs offense must do so.

An old football cliché is “throw to score, run to win.” The implication is that running the ball is the superior method of hanging onto a lead. Eventually, this is true. The probability of a turnover on a run play is just 0.6%, compared to 2.9% for passing plays, according to The Athletic contributor Ted Nguyen. There’s also the risk of not being able to keep the game-clock running if there is an incomplete pass. The problem with playing to run out the clock kicks in when teams do it too early. The trade-off offenses make in securing lower risk of turnovers by running the ball often is a higher likelihood of a three-and-out.

This downside is especially pronounced against Mahomes. According to The Athletic contributor Ethan Douglas, Mahomes’ average passing EPA is negatively correlated with the Chiefs’ win probability. To put this in English, the Chiefs are expected to score more points when their backs are against the wall than when the game is going well for them. This is a massive outlier from quarterbacks in general, but also the greatest quarterbacks of the past two decades. When playing with a lead, defensive linemen can normally pin their ears back and rush the passer without worrying about gap discipline.

That doesn’t apply to Mahomes who is the master of finding new launch points and improvising from them. In a recent post, FiveThirtyEight contributor Josh Hermsmeyer showed that limiting Mahomes’ time to throw doesn’t impact his QBR. As of the end of 2019 (the most recent data I found), NextGenStats reported that Mahomes was the only quarterback with net-positive EPA (+0.07) on dropbacks of longer than 4 seconds since 2017. The league-average was -0.57 EPA on these plays, but it’s even more astonishing that Russell Wilson ranked second and still only averaged -0.29 EPA. This was the best way I’ve seen of quantifying just how much more dangerous Mahomes is than every other quarterback.

The chart above shows the performance of recent great quarterbacks’ best three-season period. When win probability is less than 50%, Mahomes’ average EPA exceeds that of Peyton Manning (2003-2005), Aaron Rodgers (2011-2013), Brady (2007-2009), Philip Rivers (2008-2010), Drew Brees (2009-2011), Wilson (2012-2014), and Ben Roethlisberger (2016-2018). And it’s not even close. No quarterback has ever given his team a better chance to come back than Mahomes.

The last Super Bowl should be viewed as a cautionary tale for what happens to teams that play conservative with a lead against the Chiefs. With 12 minutes remaining in the fourth quarter, the 49ers had the ball and a 20-10 lead. They committed the cardinal sin of running the ball on 1st-and-10, got lucky in converting the first down a play later, and then ran the ball again on 1st-and-10. Their luck ran out as that run only yielded one yard and they had to punt three plays later. The Chiefs scored a touchdown on the following drive to narrow the 49ers’ lead to 20-17.

When the 49ers got the ball back, they ran the ball on 1st-and-10 again. A five-yard gain isn’t a bad outcome per se, but it’s inferior to a pass which yielded 7.1 yards on average for Jimmy Garoppolo that day. The margin for error is lower when these yards are left on the table. Unfortunately, for the 49ers, they picked a bad time to throw two incomplete passes. They then punted on fourth down and Mahomes went on to lead the game-winning drive. By the way, this is all glossing over Kyle Shanahan’s bad decision to run the ball to kill the clock with just one minute remaining in the first half.

This season, the Miami Dolphins made similar mistakes which likely left points on the table in a close 33-27 Chiefs win. They first jumped out to a 10-0 lead in the first half and then allowed a touchdown on defense. After a Chiefs’ penalty which reset the downs, the Dolphins opted to run the ball on 1st-and-10 and gained just 2 yards. That play was followed by a sack on 2nd-and-long and a broken play on 3rd down which led to a punt. Luckily for them, the Chiefs go three-and-out and they have another opportunity to build a bigger lead. A first down pass picks up 12 yards, but it’s followed by a run play on the next 1st-and-10 which only picks up 3 yards. Tua Tagovailoa proceeds to throw an incompletion on 2nd-and-7 and an interception on 3rd-and-7.

The pattern in these examples should be clear. Mistakes on these longer 2nd and 3rd downs are more likely because of the lower margin for error induced by conservative first-down play-calling. The Chiefs went on to take a 30-10 lead, but the Dolphins offense came alive with a pass-heavy game script in the second half. Without the Dolphins’ first half conservatism, it’s reasonable to think the outcome may have been different.

The Bucs’ offense is fueled by explosive plays, not methodical drives

These cautionary tales particularly apply to the Bucs who have been atrocious on first down throughout this year. They rank 25th in passing percentage on competitive 1st-and-10s. This run-heavy disposition is a drag on their overall success rate. But even when run and pass 1st-down plays are segmented, the Bucs stink at both! Their passing success rate on these plays is 48% compared to the league average of 55%; only the Eagles and the Broncos had lower success rates than them. They ranked dead-last on 1st-and-10 runs with a 34% success rate, four percentage points lower than the 2nd-worst team.

The weirder aspect of this offense is that they are weak in almost every down-and-distance, not just 1st down. While Byron Leftwich becomes much more in synch with analytics on competitive 2nd-and-longs (the Bucs pass 79% of the time, third-most in the NFL), the Bucs’ success rate is still below league-average on both the run and pass. 2nd-and-medium is essentially a dealers’ choice and the Bucs opt to be the most pass-heavy team then. But they only achieve a passing success rate for these plays of 53% which is just below the league-average of 54%. 3rd-and-long has a low-percentage success rate for any offense, but the Bucs don’t even pick up margins here, as they rate below league-average again.

So if the Bucs are inefficient on almost every down-and-distance, how is it that they rank 2nd in scoring and have reached the Super Bowl? The answer is that they make their successes really count by accumulating explosive plays. The Bucs ranked 3rd, behind the Texans and the Chiefs, with 67 gains of 20+ yards in the regular season. Methodical drives become a lot less important when a team can rip off long touchdowns and put six points on the board at the drop of a hat. The question for the Bucs is whether that explosiveness is enough to overcome the Chiefs. The Chiefs offense had even more explosive plays and are much more efficient.

In the Week 12 matchup, the Bucs got shut out on 20+ yard gains on each of their first four drives. It shouldn’t be assumed their start in the Super Bowl will be as lethargic. They finished the Week 12 game with five explosive plays. Brady turned to a familiar tactic from his days in New England to pick up two of them: unleash Rob Gronkowski in the middle of the field. This was a particularly strong answer against the Chiefs. Kansas City ranks 6th in usage of Cover 2 (19.8% of regular season snaps) and 3rd in usage of 2 Man (13.2%). Steve Spagnuolo often disguises these two-high coverages by showing one-high and then spinning a defensive back deep. The vulnerability of two-high coverages is the hole between the two deep zones. Gronkowski is an ideal weapon to exploit it.

In this example, the Chiefs set up a 5-man rush for a zone blitz, a classic from Steve Spagnuolo’s mentor from his days with the Eagles, Jim Johnson. This is a counter to the Bucs’ empty set. By threatening six potential rushers, the offense shouldn’t be able to release five receivers. That would leave one unblocked rusher. Cover 2 is designed to flood the shallow area beyond the line of scrimmage with five defenders which would be more than the four receivers who release.

A zero blitz would still be a daring call in this situation because of the possibilities that Gronkowski will release (which is what happens) and that the offensive line buys Brady enough time to find him wide open in the seam. Spagnuolo is the one who blinks in this game of chicken by opting for just the 5-man rush; Alex Okafor is tasked with carrying Gronkowski into the hole. This is a horrible matchup for the Chiefs. Rashad Fenton has to account for Chris Godwin’s vertical route, while Juan Thornhill is eyeing Mike Evans. There’s no one to help Okafor with Gronkowski.

On the first drive of the second half, the Bucs used Gronkowski as a wrecking-ball against another Cover 2 look by the Chiefs. The generally run-heavy under center formation influences the Chiefs to rotate Daniel Sorenson into a Sky assignment—the safety is the force defender against outside runs, instead of a cornerback who is smaller. This allows Charvarius Ward to stay on Evans if he runs a vertical route which is exactly what happens. It’s normal Cover 2, but with the safety and cornerback trading assignments.

The Flood, or Sail, concept Leftwich calls is a classic zone-beater. Three receivers—Evans, Gronkowski, and Fournette—will be stacked along the numbers at three different depths. Zone defenses consist of deep and shallow zones, so a three-level stretch overwhelms that coverage structure. The added effect of play-action—a common tactic of Brady’s in New England that Leftwich began dialing up later in the season—makes linebacker Damien Wilson keep his eyes on Fournette. Sorensen and Wilson are both eyeing Fournette, while Gronkowski slips into the grass between the two levels of the defense.

The damage Gronkowski can do in the middle of the field opens so many other possibilities. The Trips Nub formation—three receivers split out on one side and an in-line tight end isolated on the other—is one the Bucs lean on when they want to get Evans, Godwin, or Antonio Brown open. The attention that Gronkowski gets means there should be space for someone among the Murderer’s Row on the trips side. It was this look that generated a 44 yard reception in the second half.

This time, the Chiefs ran a variant of Tampa 2 which effectively bracketed Evans and Gronkowski. Wilson and Tyrann Mathieu have Gronkowski covered in the deep and underneath zones to the right. Linebacker Ben Niemann carries Evans up to Fenton who becomes the hole defender. This leaves Ward on an island with Brown, and Thornhill on his own with Godwin. Spagnuolo’s play-call wasn’t a bad one. It’s not possible to double everyone, as much as that guy at the bar otherwise insists (if you don’t know who he is, it’s probably you). The pressure—a 5 man blitz disguised as a 7 man blitz—got home quickly. Thornhill, a good safety, just got beat by an elite receiver. The luxury of having this many elite receivers is that there will always be at least one defensive back who must win a tough one-on-one matchup. That’s how the Bucs get the proverbial biscuit.

Why Steve Spagnuolo’s Cover Zero blitzes may be the kryptonite for the Bucs’ explosive plays

Spagnuolo seems to relish devising game-plans against Brady. His most famous one was for the New York Giants’ shocking 17-14 win in Super Bowl 42 over the historically explosive 2007 New England Patriots’ offense. The formula for beating Brady was leaning on a 4 man rush featuring Michael Strahan, Osi Umenyiora, and Justin Tuck to get pressure with 7 in coverage. It paid off that day, as the Giants earned five sacks and held the Patriots offense to just 4.0 yards per play.

Data suggests this is no longer the best way to attack Brady. This season, Brady ranked just 19th with 0.1 EPA per play when defenses rushed five or more, compared to 6th with 0.24 EPA per play when defenses rushed four or less. This bodes well for Spagnuolo who normally sends the house frequently. The Chiefs defense ranked 7th with blitzes on 35.2% of passing attempts. Even more notable, the Chiefs led the NFL with a Cover 0 frequency of 9.3%. For perspective, the Bucs ranked 4th in Cover 0 blitzes and had a frequency of 4.6%, less than half the Chiefs’ rate.

| Defensive Performance by Blitz Type | |||||

| Blitz Type | Plays | Avg. Rushers | EPA Per Dropback | Positive% Allowed | Boom% Allowed |

| Zero Blitz | 614 | 6.0 | -0.09 | 40% | 24% |

| Man-Free (Cover 1) Blitz | 7896 | 5.3 | -0.01 | 45% | 25% |

| Zone Blitz | 3041 | 5.2 | +0.07 | 48% | 24% |

Cover 0 is a man-coverage blitz that sends everyone except the defenders assigned a receiver. It sounds dangerous because, by definition, every defender is left on an island. That sounds especially dangerous when the likes of Mike Evans, Chris Godwin, Antonio Brown, Rob Gronkowski, or even the speedy Scotty Miller are the ones on those islands. Yet, Football Outsiders has found that Cover Zero blitzes average a lower EPA per dropback than “safer” man-free blitzes or zone blitzes, and roughly the same Boom percentage (percentage of plays in which the defense allowed an EPA of 1.0 or higher). There aren’t a lot of defensive play-calls that achieve stable efficiency, but the Cover 0 blitz is one of them.

The Chiefs’ disguise of their coverages truly pays off when it sets up these kind of pressures. The Bucs had a cool play-design on a 3rd-and-3 for a basic Mesh concept that was preceded with Brown shifting into the backfield. His assignment is to run the wheel route down the sideline. The Chiefs don’t tip their hand when Brown shifts into the backfield; Thornhill (Brown’s man) bumps over slightly, but the cornerbacks’ eyes are on Brady as if it’s zone.

The Chiefs’ 6-man blitz simply outnumbers the Bucs’ line which is using a half-slide away from All-Pro defensive tackle Chris Jones. The line actually does a good job picking up the three-man stunt. Right tackle Tristan Wirfs smoothly passes off Daniel Sorensen to right guard Alex Cappa and engages Niemann when he loops into the C-gap. The problem is there’s simply no one who can pick up Tanoh Kpassagnon. It’s basic math: six is more than five.

It’s not like the Bucs had a great alternative protection they could have run either. Mesh depends on having answers to both man and zone. The answer to zone is the sit route Gronkowski runs behind the two crossers, so keeping him in to block is undesirable. And using Brown in pass protection is obviously a bad idea. It’s an impossible situation for the offense unless Brady can diagnose the pressure or coverage before the snap. The Chiefs’ intricate disguises left him helpless. Still, additional problems that come from keeping Gronkowski and a running back in pass pro too surfaced later in the game.

The Chiefs’ play-call on the interception Brady threw to Bashaud Breeland was not a Cover 0 blitz, but it did involve a 7-man rush. It was a man-free blitz that had a Green Dog call. A Green Dog call means that when a player—typically a tight end or running back—stays in to pass protect, the cover man has the green light to join in on the blitz.

The protection appears to be a type of full-slide to the right where Gronkowski takes the backside edge rusher. Mathieu is assigned Fournette in coverage and instantly executes the Green Dog blitz. The Chiefs called a similar three-man stunt as the one they used on the earlier Cover 0 blitz. The entire right side of the line again deserves props for picking it up, with Wirfs stalling linebacker Anthony Hitchens upon impact, Cappa attacking Okafor, and center Ryan Jensen pivoting on the fly to handle the slant by Jones. This play is a perfect example of why keeping the running back in to protect is worse in practice than in theory.

It also bears mentioning that Cappa suffered a broken ankle in the Wild Card Round and has been replaced by Aaron Stinnie. This gives the Chiefs a mismatch. According to ESPN, Jones had the second-highest pass rush win rate among defensive tackles, only behind Aaron Donald. The Bucs will likely use protections which allow for double-teams like Big-on-Big or play-action off Duo, so that Jensen or Wirfs can help Stinnie against Jones. This is where the Chiefs’ blitz and stunt packages kick in. The threat of these multiple pass rush attacks should leave the Bucs with little choice but to isolate Stinnie on Jones at times.

Football Outsiders backs up the idea that the more important determinant for pass rush success is the raw number of pass rushers, not the difference between rushers and blockers (see chart above). Gronkowski is a freak of nature talent who actually excels at pass protection, but this is not true for most tight ends. The Bucs’ running backs—Fournette, Ronald Jones, LeSean McCoy, and Ke’Shawn Vaughn—are a lot more human in that regard. When Leftwich keeps one of them in to block, it sounds in theory like he’s buying Brady more time. What he’s really doing is inviting more defenders into the backfield and giving the Chiefs an easy matchup they should be able to win.

NFL NextGenStats data provides an additional reason for Spagnuolo to bring the heat against Brady in this rematch. Relative to most of the league, Brady does not move much in the pocket. In contrast, a reason why I would not advise Bowles to use Cover 0 against Mahomes is because he throws from so many different launch points. It’s maddeningly difficult to anticipate what the ideal rush lane should be against Mahomes, but it’s predictable against Brady. The Bucs’ offensive line is talented, but this is all the more reason to either put the onus on Brady to avoid a free rusher or get the Bucs to keep their running backs in to block. It can be a high variance strategy, but it’s one that pays off with commitment.

Getting into short-yardage downs sets up the Bucs’ run game to succeed

A successful version of the Super Bowl for the Bucs may indeed involve their run game, but not the way that “Run the Ball” enthusiasts typically imagine. The Chiefs defense has allowed the 7th-highest success rate on both competitive 2nd-and-short (79%) and 3rd-and-short runs (76%). If the Bucs create lots of 2nd-and-short and 3rd-and-short situations by passing efficiently on 1st down, the ground game should thrive. It’s a reversal of the “run to set up the pass” cliché.

To that point, Bucs’ run game ranks 5th in the league with an 81% success rate on competitive 2nd-and-short plays. They also rank 1st in yards per carry on those down-and-distances with a blazing 7.1 yards per carry, edging the 2nd-ranked Titans by 0.3 ypc. For perspective, the gap between the 1st-ranked Bucs and the 5th-ranked Packers on these plays is 2.5 ypc. It’s an astonishing contrast from their run game on competitive 1st-and-10s in which they rank dead-last in success rate by 4 percentage points. Short-yardage downs transform the Bucs’ run game from the worst in the NFL into one that’s more efficient than those with Derrick Henry and Aaron Jones.

The best explanation for this disparity is that the Bucs’ main run concepts are geared for grinding out yardage in the interior. They’re not built around Outside Zone like the Rams, 49ers, Titans, Packers, or Browns. They also don’t use pullers on off-tackle runs like Power O so frequently the way the Erhardt-Perkins teams like the Bills, Dolphins, Texans, and Patriots (basically the Belichick tree) do. Instead, their two key run schemes are Inside Zone and Duo.

Inside Zone and Duo look so similar that tweets which say “Inside Zone or Duo?” and embed a clip of a run play are a recurring bit on football-related social media. Blocking assignments for Inside Zone are simple, in that the base version assigns each lineman a “zone” in the direction of the play-side. Blockers with defensive linemen in their zone are “covered”, while blockers with no defensive linemen in their zone are “uncovered.” An uncovered blocker will double-team a defensive lineman with a covered blocker until one can peel off in their zone to block a linebacker or defensive back. The difference with Outside Zone is the footwork. Instead of taking a bucket step as they do on Outside Zone, the blockers drive-step forward with the intent of pushing the front off the line of scrimmage in a straight line.

Former NFL offensive tackle Geoff Schwartz created a handy flow chart which spells out Duo’s differences with Inside Zone. First, the backside guard will still use Inside Zone footwork, but the center will back-block instead of stepping to the play-side. For the center, it’s like he’s back-blocking on Power O, but the backside guard provides help instead of pulling. Second, the backside tackle is blocking the defensive end instead of stepping to the play-side. In Inside Zone, he helps the “covered” tight end until he peels off to the play-side. The idea of these techniques is to create double-teams (hence, the name “Duo”) across the interior. It’s not ideal for creating big gains, but it’s useful for converting short-yardage downs.

This 34 yard run on a 2nd-and-1 by Ronald Jones was the Bucs’ longest rush of the day in Week 12. Is it Inside Zone or Duo? If you guessed Duo, congratulations on being right. If not, review the flow chart again. Then go watch Jensen (center) and Wirfs (backside tackle). After that, watch how the left side of the line is doing textbook Duo blocking. Left guard Ali Marpet and left tackle Donovan Smith put Jones on roller-skates. Marpet’s footwork in particular is masterful, as he peels off to attack Sorensen square in the chest.

Gronkowski puts on another clinic against defensive end Mike Danna with his play-side block, but it’s Godwin’s stalk block on Mathieu that turns this short first-down into an explosive play. The fact that Mathieu had the more advantageous angle than Godwin is what makes this effort so impressive. The finer details of blocking are ingrained in the Bucs’ players and not just the linemen.

Another 2nd-and-short run by the Bucs featured the Inside Zone. The play-side is to the right, but the beauty of zone-blocking is how it self-adjusts to the defense’s reaction. Fournette has the option to cut back and this is exactly what he does. No one will mistake Playoff Lenny for Barry Sanders, but he does just enough to get to the open C-gap between Smith and Gronkowski. Gronkowski’s block is the most important one, as the defense aggressively flows to the play-side. Because Gronkowski stood up Kpassagnon, there is a clean lane for Fournette to pick up 3 yards and the first down.

Tampa Bay’s rushing success rates on 2nd-and-short (6% above the league-average) and 3rd-and-short (4% below the league-average) may differ because there’s a drastic difference in how often they align under center. The Bucs align under center 70% of the time on 2nd-and-short, but only 34% of the time on 3rd-and-short. Across the league, run plays are more efficient from shotgun because of the ease of packaging them in RPOs or option runs involving the quarterback. But the Bucs’ specific run schemes (which work best in short-yardage plays) put a premium on push up the middle. Occupying perimeter defenders with blockers instead of having the quarterback read them works fine if the object is to gain 3 yards.

Still, Tampa Bay should be trying to run the ball more on 3rd-and-short (they do so at the lowest rate in the league). One play-design they used against New Orleans in the Divisional Round shows a blocking design that fits what they do. They align in Shotgun to keep New Orleans thinking pass and align tight end Cameron Brate on the same side as Fournette. If you haven’t already caught on, it’s Inside Zone.

The wrinkle for them is that Brate blocks the opposite direction of the line to hold up defensive end Marcus Davenport. It’s such a good tendency-breaker that Malcolm Jenkins stands still until it’s too late. Meanwhile, Wirfs drives linebacker Alex Anzalone more than five yards off the ball. Kansas City will give Tampa Bay these kinds of mismatches too, especially when Sorensen is aligned in the box. Tampa Bay can’t let up in these situations which are a huge relative strength for them.

To get into these short yardage plays, the Bucs must break tendency and win 1st down through the air

It sounds too obvious that leaning on Tom Brady in the Super Bowl is a good idea. But the Bucs really could use that advice on 1st down, given how run-heavy they are and how good their short-yardage run game is. Both offenses in this game are capable of explosive plays galore, but only the Chiefs so far have shown they are capable of methodical drives to the endzone when explosives aren’t available.

Adjusting the early down play-calling to be more pass-heavy would certainly help the Bucs’ chances, but that alone won’t be an equalizer. The Chiefs’ defense has shown commitment to sending the house and this limits the time quarterbacks have to connect with receivers vertically. Short passes—those with air yards of less than 10 yards—may be the Bucs’ key to getting around this issue. But while the Chiefs’ offense ranks second in average EPA (0.17) on 1st-and-10 passes with less than 10 air yards, the Bucs offense ranks 19th (0.02). So the Bucs don’t pass a lot relative to the league in these situations and they’re also not that good when they do pass.

The good news for the Bucs is that their best performance on these short 1st down passes came against the Chiefs of all teams. In Week 12, the Bucs averaged 0.46 passing EPA, earned a 64% success rate, and notched 8.1 yards per attempt on 11 1st-and-10s with these short throws. The Chiefs defense in general is mediocre in these situations, ranking 19th with an average of 0.07 passing EPA allowed, a 57% success rate, and 6.1 yards per attempt this season.

There is a large split in performance among the Bucs’ targets on these plays. Godwin leads the team (among those with minimum 6 targets) with 0.54 average EPA, a 78% success rate, and 7.4 yards per attempt on 9 targets. Evans (0.18 average EPA, 46% success rate, 5.7 ypa on 11 targets) and Miller (0.14 average EPA, 75% success rate, 5.9 ypa on 8 targets) also come out favorably. While Gronkowski nets positive average EPA (0.04), it’s telling that his ypa is low at 4.5.

Godwin is such a good target in these situations because he’s excellent at reading coverages in the middle of the field. An example of an 8 yard gain by him on a 1st-and-10 came against the Saints’ “Solo” Quarters coverage in the divisional round. This is a coverage the Chiefs will likely use a fair amount on Sunday. The Bucs’ concept is Hi-Lo Triple In—all three receivers in the trips set are running in routes. Godwin patiently waits for linebacker Demario Davis to turn his back to him, and then makes his break. It would benefit the Chiefs to align L’Jarius Sneed on Godwin because he has the lowest passer rating allowed of the remaining defensive backs on either team. He’s the one Chiefs defender who seems to hold up well against elite slot receivers (for more on Sneed, check out this post by Doug Farrar).

So I knew Godwin was excellent and worthy of Sneed’s attention. But I was surprised by two other aspects of the Bucs offense on these downs: (a) how surprisingly inefficient Brown is, and (b) how surprisingly efficient Fournette is. Brown’s average EPA on these short 1st-and-10 passes was approximately 0.00 and his success rate was 50%. AB may be the household name, but Miller seems like the clear superior choice to join Godwin, Evans, Gronkowski, and Fournette as the main eligible receivers on 1st down. It may make sense to substitute Brown sometimes and use him as a decoy on the outside, but Miller’s actual targets are more productive.

Still, the Fournette angle is the more interesting one to me. He ranked second among all Bucs players with 0.20 EPA, third with a 59% success rate, and third with 6.4 ypa on 27 short 1st-and-10 targets (the most of anyone). This gave him a huge edge over Jones who had -0.37 average EPA and a 28% success rate.

This may really matter in the Super Bowl because the Chiefs’ defense allows a higher average EPA on short 1st-and-10 passes to running backs (inclusive of fullbacks) than wide receivers or tight ends. They allowed 5 catches for 1.02 total EPA to Austin Ekeler, 3 catches for 0.88 total EPA to Devin Singletary, and 4 catches for 0.30 total EPA to Alvin Kamara. Those are just the running backs who got a significant volume. David Johnson, Mike Burton, Christian McCaffrey, and J.K. Dobbins each caught one reception which was for 0.30 EPA or greater too. Running back targets typically aren’t efficient, but the Chiefs defense changes the calculus here.

There were hints of the Bucs’ running backs’ effectiveness as receivers in the Week 12 matchup too, as Jones earned 1.52 EPA on a touchdown reception and Fournette earned 0.63 EPA as well. Fournette’s first gain is seemingly unremarkable, with it being just an 8 yard pickup. But the thing that’s really worth stressing is why it worked. The Chiefs had been playing Cover 4 to account for the vertical threats posed by Evans, Godwin, and Brown. Cover 4’s weakness is the flats. This is accentuated by how deep of a drop Fenton takes here. It’s a key weakness of the Chiefs’ zone coverages. It’s also vintage Brady to take the easy 5 yard throw when defenses give it to him.

The best types of play-designs for the Bucs may be a lot like those Brady had executed in New England. Coincidentally, they overlap with the Chiefs’ own staples. The above gif is the very next play after the previous gif. Running a concept called Tosser (in the Patriots’ Erhardt-Perkins system verbiage) to one side with Godwin and Brown executing slants, while Fournette runs a flat route, seems to accentuate the Bucs’ strength. The route combination creates a natural pick on Niemann and gives Fournette a cushion.

For those who wonder whether I’m on the right track with Leftwich’s headspace, the very next play after that was a sit route to Godwin which picked up 10 yards. The Chiefs had been attempting a man-free blitz, but the design gave Godwin a huge cushion which allows Brady to easily connect with him. The explosive plays will come for the Bucs, but the true X-factor in the Super Bowl is whether they can drive down the field in boring, unremarkable ways. It’s the one tried-and-true method that’s won Brady six Super Bowls to date and gives him the best shot at a seventh.

Other things that may matter

The kickers

Frankly, neither kicker has had a great season to date. Personally, I put a lot of weight on extra-point percentage because there is a large sample of them. The attempts are apples-to-apples comparisons with each other. Bucs kicker Ryan Succop happens to rank 31st with a 91% success rate on extra-point attempts, while Chiefs kicker Harrison Butker ranks 36th with an 89% success rate. Granted, neither Succop nor Butker have missed a field goal attempt of less than 40 yards this season. I would still caution both coaches against overconfidence in their kickers when making 4th down decisions, especially when the ball is between the opponent’s 33 yard-line and midfield.

The Chiefs’ kick return vs. Bucs’ kickoff team matchup

The special teams on both sides in general are bad. This means that, most of the time on punts and kickoffs, that the battle is a wash. There is one exception though, as the table below indicates.

If Bucs’ punter/kickoff specialist Bradley Pinion fails to force a touchback, the Chiefs’ kick return team may be in a position to exploit an awful Bucs’ kickoff coverage team. The blocking scheme the Chiefs used on a Byron Pringle kick return touchdown is quite similar to the one other teams have used repeatedly against the Bucs to produce long returns.

Watch the left side of the Broncos’ kickoff coverage unit. The two men closest to the sideline are allowed to charge past the Chiefs’ first line. This is because the Chiefs’ upbacks directly in front of Pringle are about to trap-block them. The next two Broncos players then both get double-teamed by the Chiefs’ first line. These double-team blocks create an alley for Pringle who is then off to the races. Those types of blocks are also the common weakness in several of the Bucs’ kick returns allowed.

For instance, this one against the Panthers in which the returner took the ball up to the Bucs’ 4 yard-line.

And another one against the Giants.

Lastly, check out how deep Bears’ kick return phenom Cordarelle Patterson is in the endzone when he catches the kick. Against most teams, this would be a crazy decision. But the Bucs’ kickoff coverage unit is so poor that it’s worth taking a flier on a big play. Pinion forces a high percent of touchbacks (86%), so they may have to take a chance the way Patterson did to exploit their advantage.

Backup quarterbacks

The AFC Divisional Round game against the Browns briefly provided a glimpse of what the Chiefs would look like with Mahomes sidelined by an injury. Chad Henne famously filled in to execute a 13 yard scramble on 3rd-and-14 and the gutsy 4th-and-1 sprint-out pass which sealed the game. There was an unsurprising dropoff in production between Henne and Mahomes that day. Compared to Mahomes’ 0.36 EPA per play and 62% success rate against the Browns, Henne earned a 0.00 EPA per play and 44% success rate. It wasn’t pretty, but Reid managed to squeeze just enough out of the backup.

The first few plays when Henne entered the game featured RPOs and some quick game concepts like All Curl and Slant-Flat. The best throw of the game he had came off an RPO which packaged a Split Zone run and a fade route by Hill. Reid seems to trust Henne with quick decisions. The issues come when he has to push the ball down the field, as he tried on an ill-fated play-action pass that got intercepted in the endzone. Hill and Kelce were still generating high EPA with Henne in the game, but the Chiefs’ other weapons became less potent.

Meanwhile, Bucs’ backup quarterback Blaine Gabbert made one lengthy appearance in garbage time against the Detroit Lions during which he attempted 16 passes. He earned an unremarkable -0.01 EPA per play and a 31% success rate that day. Stylistically, he’s basically the opposite of Henne. There’s plenty of arm strength, but also over-aggressiveness in trying to hit underneath routes. In many ways, Gabbert fits the part as the backup for this high-variance offense.

Gabbert targeted Evans 5 times in the game, so that’s a tendency to watch in the Super Bowl if Brady has to exit. The Lions’ sad bastardized effort at Cover 3 left plenty of opportunities for Gabbert to attack deep, whether it was up the seam or down the sideline as it is in the above gif. The way the Chiefs confuse much better quarterbacks with their coverages should allow them to avoid similar issues.

This section may all be moot, of course. Alternatively, one of these two quarterbacks may have to emulate Nick Foles.

4th down tendencies

An underrated reason why the Chiefs won last year’s Super Bowl was Reid’s willingness to go for it on 4th down. On their second drive of the game, the Chiefs had the ball on the 49ers’ 5 yard line for a 4th-and-1. Rather than settle for the field goal, Reid unveiled a trick play reminiscent of the Single-Wing offenses of the early 20th century. Mahomes shifted away from the center and the ball got snapped directly to Damien Williams who pushed through the hole for 4 yards. On the next play, Darwin Thompson scored a touchdown. All else equal, opting for a field goal instead meant that the game would’ve been tied 20-20 in the fourth quarter when Williams caught the actual game-winning touchdown pass. Sure, the Chiefs may still have won the game. Williams ran for a 31 yard touchdown on the following drive, albeit against a stacked box which went all-in on stuffing the run at the line and missed.

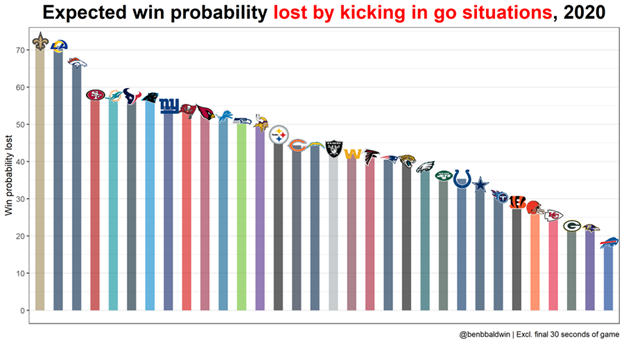

Those familiar with Reid in his time with the Eagles and his early years with the Chiefs remember him as one of the most conservative coaches on 4th downs, but he appears to be a changed man now. The Chiefs ranked 11th in 4th down aggressiveness in the first 12 weeks which Ben Baldwin analyzed.

Meanwhile, the Bucs ranked 31st in 4th down aggressiveness. Arians did break that tendency in that NFC Championship Game by successfully converting a 4th and 4 from the Packers’ 45 which preceded Miller’s deep touchdown catch before halftime. It would behoove him to do so again when he desperately needs to steal points like no other time.

The bigger issue for Arians may be 4th down decisions in field goal range. The Bucs ranked 9th-worst in win probability lost by kicking in situations that optimally are “go for it” decisions. The most egregious example for the Bucs was in Week 5 against the Bears on a 4th-and-1, and Arians settled for a field goal to take a 19-17 lead. The Bears then got a field goal of their own and won the game 20-19 right after. The decision to kick alone cost the Bucs 8% win probability, according to @edjsports. Incidentally, the Chiefs ranked 4th-best. This is a decisive advantage for the Chiefs.

Who’s going to win

As a contrarian by nature, I have some reluctance to pick the Chiefs, but that’s what I’m going to do. The best way to reach this conclusion is to imagine what a Bucs win would look like. On the defensive side: The Bucs’ defensive line owns the Chiefs’ injury-plagued offensive line (plausible, even likely). The Chiefs respond by running the ball on early downs more which leads to extra 3rd-and-longs and extra punts (possible). Bowles abandons his typical heavy-box tendencies (unlikely). Mahomes struggles under duress (even less likely).

On the offensive side: The Bucs generate enough explosive plays to match the Chiefs’ (plausible, even likely). The Chiefs struggle to contain the Bucs’ receivers—especially Godwin, Fournette, and Miller—on early downs, Gronkowski shreds their two-high coverages for explosive plays, and the Bucs have many opportunities to run the ball down their throat in short-yardage (all possible). Leftwich abandons his typical run-heavy tendencies with the worst early-down run offense (unlikely). Brady overcomes his usual struggles against the Chiefs’ 6 and 7-man blitzes (even less likely).

The Chiefs certainly have deficiencies too, but it’s much easier to imagine how they overcome them. Hill was the bane of the Bucs’ existence in Week 12. So he’s very likely Reid’s Plan A to exploit Bowles’ defense. If Bowles finds a formula to contain Hill this time—maybe it includes Cover 6, Cover 7, Cover 4, pattern-match Cover 3, Cover 1 with a bracket on Hill—there are logical counters. The Chiefs’ primary adjustment when teams do take Hill away is to lean on Kelce to carve them up 8 yards at a time. Perhaps there’s a way the Bucs contain both; the defensive line may pressure Mahomes before Hill can get open deep and while Kelce is doubled. Hill can be deployed in jet motion to create seams for Edwards-Helaire, Hardman, or Sammy Watkins (fresh off IR) who all have plenty of speed. Reid’s packages of RPOs, screen passes, bootlegs, and traditional dropback West Coast concepts are second to none too.

Mahomes’ ability to always keep his team in the game—no matter the deficit, no matter how much pressure he faces—means that the opposing offense must be one that never take its foot off the gas. That doesn’t sound like the Bucs’ offense, given their early down tendencies and fourth-down conservatism. The Chiefs can blitz so aggressively because they can count on Mahomes to get his points. This is a safe play against Brady whose launch points are among the most predictable in the league. It’s also a necessary tactic to create pressure in this matchup because the Bucs’ offensive line is a strength. Forcing the issue by making Jones and Fournette pass protect (or removing Gronkowski from Brady’s progressions) is the best chance of disruption. Further, the Chiefs defense disguises their intentions better than nearly anyone in the league. Brady is perhaps the most cerebral quarterback in history, but even he consistently gets thwarted in guessing Spagnuolo’s hand. Of all matchups in this game, my confidence is greatest in the Chiefs’ front to win the pass rush battle.

The Bucs absolutely have a realistic path to win this game and make me sound like an idiot. But waffling is no fun. I’m taking a side. I’m with the new GOAT, not the old GOAT.