There are many types of coaches who have won Super Bowls. Coaches who had previously been offensive coordinators, defensive coordinators, and even a special teams coordinator. “Retreads” who failed in their first NFL head coaching job, but fared better in their next. And for those haters of college football coaches, Jimmy Johnson came straight from the University of Miami with a newfangled defensive philosophy—smaller, speedier personnel for the 4-3 scheme—and established a dominant Dallas Cowboys dynasty (Barry Switzer came straight from the college ranks too, but let’s be real). No candidate should be ruled out because of what their background is.

However, I do think there are guidelines owners should follow that increase their likelihood of success. The chart above is a bit technical, but it shows that offensive performance is more stable over time than defensive performance. It also shows that passing offense performance more closely follows total offense performance than run offense performance. A head coach doesn’t have to be a former offensive coordinator or quarterback guru, but he should demonstrate convincing knowledge of offensive trends if he is not one; good recent examples of this type of coach would be Buffalo Bills head coach Sean McDermott or Tennessee Titans head coach Mike Vrabel. If the head coach is totally dependent on taking a blind shot in the dark on his offensive coordinator, this is not a formula for sustained success. That coordinator will likely soon become a head coach himself for another team (think Dan Quinn’s hire of Kyle Shanahan and the Falcons’ rapid regression after Shanahan left for the 49ers).

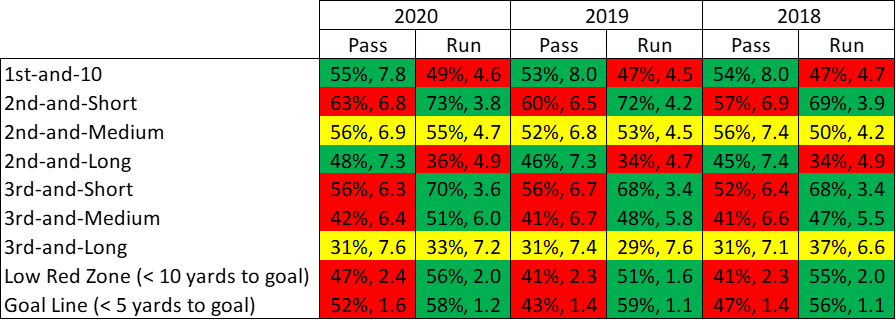

There are also consistent leaguewide patterns on when it is best to pass and when it is best to run. There’s a lot more to good play-calling than simply picking “run” or “pass” on a given play, but it does improve a team’s likelihood of success to be in synch with the analytics here. From Warren Sharp, this is the breakdown of success rate and yards-per-attempt on down-and-distance segments:

Sample only includes plays in competitive situations (lead of 16 points or less for either team);

Short = 1-3 yards to first down, Medium = 4-7 yards to first down, Long = 8-10 yards to first down;

Green = dominant strategy, Red = inferior strategy, Yellow = no dominant strategy for situation

Success rates are a straightforward measurement of offensive consistency. A play is considered a “success” based on whether the ball-carrier or receiver gained 40% of needed yards on first down, 60% of needed yards on second down, or 100% of needed yards on third or fourth down. It’s a common misperception for people to believe that analytics implies teams should always (or almost always) pass. NFL data does show that passing is consistently the more successful (or dominant) strategy on 1st-and-10 and 2nd-and-Long. But there are other situations like 2nd-and-Short, 3rd-and-Short, 3rd-and-Medium, and plays in the Low Red Zone when running the ball is consistently the dominant strategy. There can be outliers who run the ball well on 1st-and-10 or pass well on 3rd-and-Short, but history suggests that’s not a sustainable tendency. I believe that a coach’s tendencies on these down-and-distance segments is a vital piece of information.

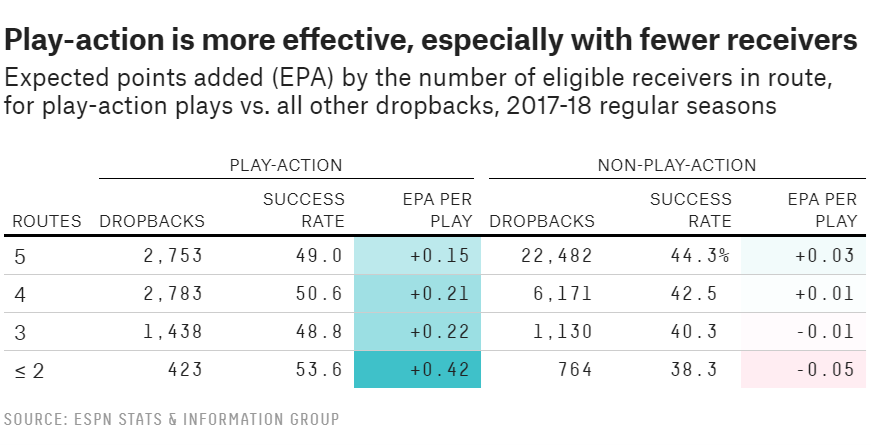

We also know that not all passes are created equal. FiveThirtyEight contributor Josh Hermsmeyer wrote how the most efficient type of play, by far, is the play-action pass. He uses a statistic called expected points added (EPA) to illustrate this. EPA measures the value of individual plays in terms of points; it’s a superior alternative to yards per play because the latter doesn’t account for differences in down, distance, or field position on different plays. For example, a 1-yard gain on 3rd-and-1 is much more valuable than a 1-yard gain on 1st-and-10; a 4-yard gain on 3rd-and-10 from your opponent’s 35 is more valuable than one on your own 35 because the former materially increases the likelihood of a successful field goal.

Play-action passes consistently generate higher EPA than non-play action passes, regardless of how many men are in pass protection and how many are running routes. The differential in average EPA is so huge that it’s impossible to conclude anything other than teams should be calling them more. So why don’t teams already do this?

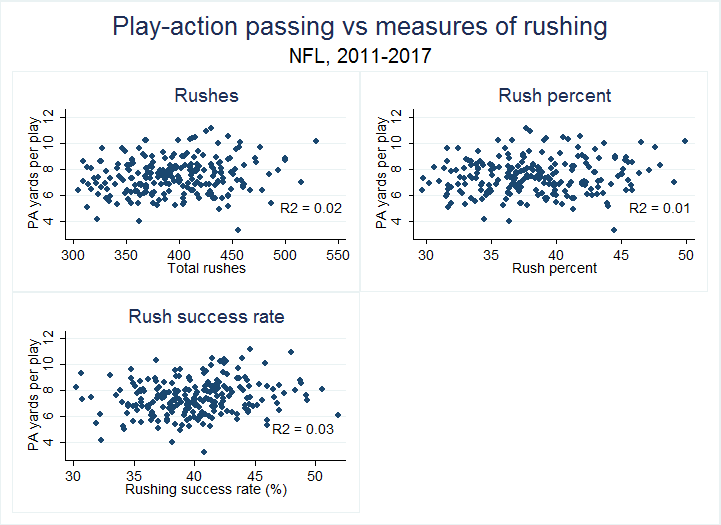

A common fallacy in football is that offenses must “establish the run” (meaning, run the ball early and often in games) before they can use play-action passes. Ben Baldwin’s post in Football Outsiders showed that there is no statistical correlation between number of rushes (or rushing percentage) and play-action yards per attempt. There is also no correlation between rushing success rate—how well a team runs the ball—and play-action yards per attempt. Here’s a useful example: on competitive plays (scoring margin of 16 or less), the Chiefs passed the 2nd-most during their historically good 2018 season. According to Football Outsiders, they still ranked 7th in percentage of passing attempts with play-action and were 6th in DVOA (a performance statistic which controls for quality of opponent) on those plays.

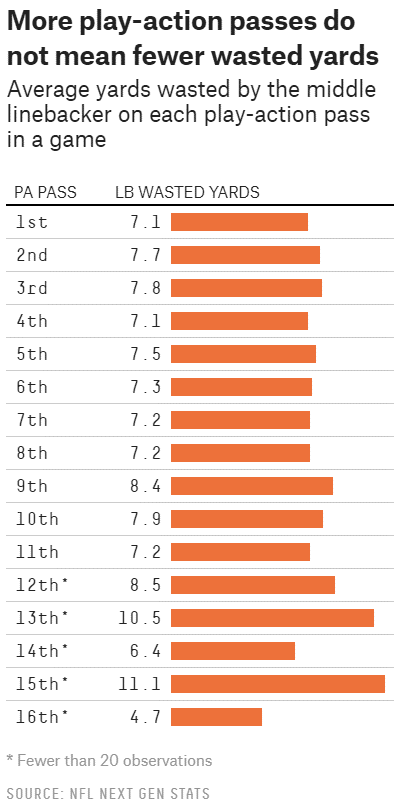

Another Hermsmeyer post used data which tracked players’ movements. This data showed that linebackers run about the same number of yards in reaction to a play-fake on the 1st play-action pass of a game as they do on the 11th play-action pass of a game (sample size is too small on attempts beyond that). There is no evidence of diminishing marginal returns to play-action. In 2017, the Philadelphia Eagles used play-action 21 times out of 43 passing attempts (49 percent) in their Super Bowl victory versus the New England Patriots. That same year, the Jacksonville Jaguars scored a combined 65 points in two weeks when they used play-action on 54 percent of passes in their Divisional Round win over the Pittsburgh Steelers and 33 percent of passes in a close loss to the Patriots during the AFC Championship Game. There may be a limit to play-action at some point, but coaches are nowhere near it yet. There are other tactics which have backing in analytics—designed quarterback runs, motion at the snap, jet sweeps or end-arounds to receivers, quarterback sneaks on 3rd or 4th-and-1, run plays with pullers in the low red zone, just to name a few—but play-action is the one no coach should be prepared to live without.

This analytical perspective on offense is essential in evaluating candidates, but it’s not the only one. Coaches must also be “leaders of men” who attract quality assistant coaches, command the respect of their current players, entice free agents to want to play for them, and work well with the team’s front office. I couldn’t possibly evaluate every candidate in this year’s interview cycle, so I picked four who seemed the most interesting to me. They consist of two offensive coordinators I think are home-run hires, a defensive coordinator who looks like the next Vrabel or McDermott-type head coach, and one offensive coordinator I have reservations about.

If I was an NFL owner, I would most want to hire Brian Daboll to be my team’s head coach

Brian Daboll’s Resume: Buffalo Bills (Offensive Coordinator, 2018-Present), University of Alabama (Co-Offensive Coordinator and Quarterbacks Coach, 2017), New England Patriots (Offensive Assistant/Tight Ends Coach, 2013-2016), Kansas City Chiefs (Offensive Coordinator, 2012), Miami Dolphins (Offensive Coordinator, 2011), Cleveland Browns (Offensive Coordinator, 2009-2010), New York Jets (Quarterbacks Coach, 2007-2008), New England Patriots (Receivers Coach, 2002-2006), New England Patriots (Defensive Assistant, 2000-2001), Michigan State (Graduate Assistant, 1998-1999)

The strongest case for Buffalo Bills offensive coordinator Brian Daboll rests on quarterback development. Josh Allen had a 49% completion percentage at Reedley Community College in 2014. He ranks sixth in the NFL at 69% in 2020. To say that he was a project when the Bills drafted him in 2018 would be an enormous understatement. The NFL’s offensive boom has largely been fueled by high risk-high reward quarterback prospects like Patrick Mahomes, DeShaun Watson, and Lamar Jackson—none of whom were selected before pick 10. Allen was worse statistically than all of them as a college prospect at Wyoming. Fortune favors the bold, and the Bills were the boldest of all in their quarterback evaluations.

The difference between Allen and his peers who I mentioned above is that he did not thrive in the NFL right away. Allen ranked dead-last among all qualified starting quarterbacks in completion percentage during his first two seasons. Improvement this drastic is unprecedented. General manager Brandon Beane certainly deserves credit for upgrading the offense, especially with the addition of marquee receiver Stefon Diggs last offseason. But to me, there is plenty of evidence that Daboll is behind Allen’s breakout season.

The 2017 season in which Daboll served as Alabama’s offensive coordinator and quarterbacks coach seems particularly instructive. Daboll had been an offensive coordinator before with the Cleveland Browns (2009-2010), Miami Dolphins (2011), and Kansas City Chiefs (2012), and produced lackluster results. At Alabama, the presence of Jalen Hurts at quarterback and an embarrassment of riches at receiver (led by workhorse Calvin Ridley) led to a sharp schematic break from the conventional Erhardt-Perkins offense he learned as a New England Patriots assistant.

Tom Brady thrived on picking out subtle tells on the defense’s coverage and rush call before the snap. By contrast, the Spread offense tactics Daboll embraced at Alabama largely left Hurts responsible post-snap to execute simplified reads. Run-pass options (RPOs) and designed quarterback runs were all the rage on the Tide’s championship run. Daboll embraced these Spread tactics in the pros as well, and it has put Allen in positions to succeed. Allen ranks fourth in quarterback rush attempts this season and third in touchdown runs. Power Read/Inverted Veer and Quarterback Power have been highly effective run schemes in the low red zone and short-yardage situations, just like they were at Alabama. Diggs is one of the best Slant route runners in the league, and his routes made the Bills’ RPOs dynamic.

The most impressive aspect of Daboll’s play-calling to me is how in synch it is with analytics findings in specific down-and-distances. The Bills rank 1st in the NFL in passing percentage on 1st-and-10 with 60%; for perspective, the gap between the Bills and the second-ranked Eagles is larger than that of the Eagles and the eighth-ranked Bengals. The Bills also are in synch with analytics data in situations which consistently support using the run game as a team’s dominant strategy. They ran the ball at the 5th-highest rate on 3rd-and-short (1 to 3 yards to go) this season and did so at the 2nd-highest rate in 2019.

2nd-and-medium (4 to 7 yards to go) situations are considered a push between runs and passes (depending on box count), and the Bills picked their spots here well too. They tied for 4th in success rate on 2nd-and-medium runs and tied for 12th in success rate on 2nd-and-medium passes. This held up in 2019 too, as the Bills tied for 4th in rushing success rate on 2nd-and-mediums and they ran the ball the 2nd-most (their success rate on passes here was the league-average). Analytics is no guarantee of success, but it’s one helpful tool that can stabilize performance at the margins. Especially with a quarterback as volatile as Allen, it’s important to vet Daboll’s process, not just the outcomes.

One area in which Daboll’s analytics-approved instincts tie in with his background with the Patriots is his affinity for play-action. Allen threw the 3rd-highest number of play-action pass attempts this season. The Yankee concept, a two-man route combination with a deep post and an intermediate crosser from opposite sides, is a staple from the Patriots that Daboll took with him to Alabama and then to Buffalo. There’s no doubt that play-action is helping Allen’s numbers. But Allen also has the highest completion percentage off non-play action passes too, and this is a more stable metric from year-to-year.

Daboll appears to take player feedback in his play-calls, as he did for the dropback pass game when Cole Beasley asked him to include the “Go” concept. “Go” pairs a flat route with a seam read. It comes from the Run-and-Shoot offense which Beasley played in at SMU under June Jones, an unlikely source of ideas for the modern NFL. They’re not unlikely for the Belichick tree which Daboll hails from though. “I watch New England play now, and they’re running a combination of Bill Walsh, Ted Marchibroda, and run and shoot, and that’s why they’re having success,” Jones once said. “Over the years, I’ve stolen from everybody and everybody has kind of stolen from me.”

I don’t worry that Daboll will fail for the reasons he did in his offensive coordinator stints before Alabama. He’s clearly a far more gifted and open-minded play-caller at the pro level now. If anything, my concern is whether he can sustain being up to date with the newest offensive trends. Though he comes from the Erhardt-Perkins tree, Daboll reminds me most of an Andy Reid disciple. He’s not like McVay or Shanahan in having a few core concepts that he leans on every year, and then simply builds counters off of them. Reid himself is the master quarterback guru who evolves drastically to cater to that quarterback’s specific needs and lets him play out of structure. Daboll’s development of Allen is more like that than Jared Goff or Jimmy Garoppolo’s.

The upside, as we see in Patrick Mahomes, is limitless. The downside is something like what happened to Doug Pederson’s Eagles with Carson Wentz. The Eagles were ahead of the curve on RPOs and spread formations in 2017, only to develop easily predictable tendencies. In my opinion, Daboll is a gamble, but a calculated one. The things he does well are likely to be sustainable, meaning he should have a high floor. I’m willing to bet on his ceiling too.

Eric Bieniemy is a stellar second-choice who shows signs of becoming the best of Andy Reid’s coaching tree

Eric Bieniemy’s Resume: Kansas City Chiefs (Offensive Coordinator, 2018-Present), Kansas City Chiefs (Running Backs Coach, 2013-2017), University of Colorado (Offensive Coordinator, 2011-2012), Minnesota Vikings (Running Backs Coach, 2006-2010), UCLA (Running Backs Coach, 2003-2005), University of Colorado (Running Backs Coach, 2001-2002)

The Kansas City Chiefs’ offense is the envy of the NFL. They ranked 1st or 2nd in scoring each of the last three seasons, and 1st in yards per game in 2 of the last 3 seasons. There are countless stats which speak to the dominance of quarterback Patrick Mahomes. He leads the NFL in career average EPA (0.26) since 2017, ranks 2nd in average EPA versus the blitz (0.27), and ranks 3rd in average EPA on deep passes (20+ air yards) (0.72). But the most impressive in my opinion is the fact that he ranks 1st in average EPA on extended plays (4+ seconds) with 0.07. According to Next Gen Stats, he is the only qualified quarterback with net positive average EPA on extended plays. The second-best, Russell Wilson, averages -0.29 EPA on extended dropbacks. Mahomes going off script is a feature, not a bug.

Head coach Andy Reid brings a wealth of X’s and O’s knowledge to this offense, but it’s striking how much input he takes in from subordinates including Mahomes himself. Quarterbacks coach Mike Kafka told The Athletic that Mahomes has the “authority and freedom” to “make as many adjustments as necessary before the play begins.” Mahomes has also personally designed plays including a trick play used against the Carolina Panthers this year. “So far that’s one,” Reid told reporters in November. “He’s had ideas, we’ve used other players’ ideas and I’m free game. If you got a good one, let’s go.”

This collaborative approach extends to the offensive coaching staff too, and that’s where the case for Eric Bieniemy begins. Bieniemy specifically has talked about how the Chiefs coaches will often be watching college football during their Saturday night meetings to fine-tune the game plan. “While we’re having those discussions, whatever Saturday night football game is on, we’re watching and saying, ‘Hey, did you see that play?’” Bieniemy said. “You’re looking at all these different college games and you see certain offenses and seeing teams doing certain things. You can’t help but notice some of the ingenuity that’s being used at that particular level.”

Reid’s previous offensive coordinators have paid unusually close attention to college football for ideas as well. When the Chiefs traded for Alex Smith, Reid and then-offensive coordinator Doug Pederson installed the zone read and run-pass option plays Smith ran at Utah under Urban Meyer. Reid and Pederson’s successor, Matt Nagy, oversaw the execution of a halfback seam concept off jet motion they copied after watching North Dakota State film of Carson Wentz. The first iteration of that play resulted in a 78 yard touchdown by Kareem Hunt against a dumbfounded New England Patriots defense. In that same game, the Chiefs unveiled an assortment of new motions and shifts they stole from the University of Pittsburgh, having watched film of the previous season’s upset 43-42 win over the national champion Clemson Tigers.

Pederson and Nagy are useful examples for imagining what Bieniemy’s head coaching tenure might be like. Like Bieniemy, they both only called plays infrequently with the Chiefs, with Reid retaining that duty most of the time. The X’s and O’s will likely track closely to the Chiefs’, and it’s reasonable to expect the college influence to stick with Bieniemy. The 2017 Eagles used even more run-pass options than the Chiefs did that season. In 2018, the Chiefs, Bears, and Eagles ranked first to third in RPO usage. Usage of motion at the snap also is fairly similar; the Chiefs ranked ninth this season through October, while the Eagles and Bears ranked 12th and 13th. All three teams also ranked in the top 10 in shotgun usage in each of the last three seasons.

Bieniemy has a different background than Pederson and Nagy and I think that matters too. While those two got their pro coaching starts as entry-level assistants with Reid in Philadelphia, Bieniemy was first a running backs coach with the Minnesota Vikings. He was the position coach for some guy named Adrian Peterson. Yes, it would be absurd to downplay AD’s natural athletic gifts which were apparent at the University of Oklahoma; it’s not like Bieniemy unleashed that in him.

But I do think there is evidence that Bieniemy’s record tracks with running backs achieving un-godly efficient results. Only one qualified running back earned a higher single-season yards per attempt than Peterson’s record. Additionally, Jamaal Charles (who Bieniemy coached in 2013 and 2014) finished his career as the leader in yards per attempt by a landslide and one of only five rushers with a positive career average EPA since 2000. Both of his two seasons with Bieniemy as the running backs coach featured him ranking above the 80th percentile in average EPA and yards per carry.

Gambling on that level of efficiency in the run game is a risky proposition, but the efficiency of running backs in the Chiefs’ passing game may be stickier. The 2018 season featured the Chiefs being one of only two teams to earn more average EPA per running back target (1st and 2nd down) than the NFL average on targets to wide receivers or tight ends. Targets to running backs are generally wastes of plays across the NFL, but not for the Chiefs. This was not the product of a single Charles or Peterson-caliber freak either. According to Ethan Douglas, all three of the Chiefs’ top running backs—Kareem Hunt, Spencer Ware, and Damien Williams—ranked in the top five for success rate on targets to running backs. Fullback Anthony Sherman was excluded due to small sample size, but if he were included, he’d be virtually tied with Hunt for first in average EPA.

Ben Baldwin’s post on The Athletic describes in detail the superior play-designs of the Chiefs’ passes to running backs. The excellence of the screen game is quintessential Reid, going back to the days of Duce Staley and Brian Westbrook in Philadelphia. The more recent area the Chiefs have pioneered is the role of the running back as a vertical threat on seam and wheel routes; think about that concept the Chiefs stole from North Dakota State. Sharp Football Analysis found that targets to running backs beyond the line of scrimmage are far more efficient than those behind the line of scrimmage. They also found that wheel routes to running backs are far more efficient than those to receivers. Though Pederson’s Eagles and Nagy’s Bears have not replicated the Chiefs’ success at this, Bieniemy may be better-suited to do so as a former running back under Reid with the Eagles and an accomplished running backs coach.

The other compelling argument for Bieniemy is that the Chiefs’ play-calling tendencies have become more in synch with analytics since he became the offensive coordinator in 2018. On competitive 1st-and-10s (scoring margin 16 or less), the Chiefs have passed on 58%, 59%, and 53% of plays the last three seasons in order; the percentages were 49% and 51% in Nagy’s two seasons as the coordinator. The 2020 season’s run-heavier tendency is the product of defenses playing with lighter boxes; to that point, the Chiefs have been remarkably successful at running on 1st-and-10s, with a 56% success rate which is tied for third in the league. In contrast, they were below league-average in success rate on 1st-and-10 runs in 2016 and 2017. The Chiefs also have progressively increased their passing rate on 2nd-and-long (8 to 10 yards to go) each year throughout Bieniemy’s tenure (and also dating back to Nagy’s).

Reid rightly has the reputation as a pass-oriented play-caller, but the Chiefs will run the ball at times when analytics suggest it’s the dominant strategy. The Chiefs ran the ball fourth-most on 3rd-and-short (1 to 3 yards to go) in 2020, and ranked in the top 10 in this down-and-distance on 4 of the last 5 seasons. If there’s one disconnect with analytics, it’s that the Chiefs rank in the top three at passing in the low red zone (10 yards to goal or less). Still, the Chiefs’ success rate at passing in this part of the field is higher than the league-average on run plays.

I rated Daboll higher because of the enormous improvement in quarterback performance he achieved as the primary play-caller. But I don’t think anyone else has a better resume than Bieniemy. There are tangible, specific areas of the Chiefs’ offense that he was likely involved with, even with Reid being the play-caller.

Of the candidates who are defensive coaches, Robert Saleh displays the best awareness of how modern offenses work

Robert Saleh’s Resume: San Francisco 49ers (Defensive Coordinator, 2017-Present), Jacksonville Jaguars (Linebackers Coach, 2014-2016), Seattle Seahawks (Defensive Quality Control Coach, 2011-2013), Houston Texans (Defensive Assistant, 2005-2010), University of Georgia (Defensive Assistant, 2005), Central Michigan University (Defensive Assistant, 2004), Michigan State University (Defensive Assistant, 2002-2003)

Though my general preference is to hire an offensive play-caller as the head coach, I’m willing to consider a defensive coordinator or position coach if he has an exceptional grasp of the offensive tendencies around the league. It would be foolish to ignore that Bill Belichick, Mike Tomlin, John Harbaugh, and Pete Carroll are all Super Bowl winning head coaches, despite never calling plays on offense. It was crucial for them to select the right quarterback and offensive coordinator, and a candidate’s opinions on those topics should get much weight. But as the general public, we’ll never know what those opinions are. What we can base our evaluation on is how their philosophy on offense might be reflected by the way they currently coach defense.

To be honest, this was originally going to be a write-up for Los Angeles Rams defensive coordinator Brandon Staley. I was first drawn to Staley because of my thinking that, to the extent defenses can affect offensive production, it’s by influencing them to avoid passing—the dominant strategy on most downs and distances. The main tool defenses can use is box count; offenses are more likely to pass when the defense loads the box, and more likely to run otherwise. FiveThirtyEight found that box count tendencies are stable from year-to-year for defensive play-callers. They also said the Rams have lighter boxes on average (compared to a league baseline) than any other team in the league this season by a wide margin.

The second-ranked team, the Denver Broncos, is the team Staley worked for last season as an assistant to Vic Fangio. Fangio had been a successful defensive play-caller with the 49ers and Bears; his main strategy is to use two-high safety looks before the snap, with a variety of coverages being used after the snap. I mention the two-high safety looks because they’re key to understanding how defenses can use box count as a tool. If not aligned deep, that second safety normally is an extra box defender. The Fangio tree seemed the most likely of all defensive coaching trees to manipulate offensive strategy away from passing on early downs.

However, that’s not what the data on Warren Sharp’s website found. The Rams actually ranked 9th in opponent passing percentage on 1st-and-10s in competitive situations (scoring margin of 16 or less). Their opponent’s success rate also was above the league-average on these downs and distances. On 2nd-and-long (8 to 10 yards to go) in these competitive situations, the Rams’ opponents threw the ball at a higher percentage than any other team’s in the league. The Rams pass defense, of course, is exceptional with Jalen Ramsey at cornerback and Aaron Donald at defensive tackle. This is surely why the success rate at passing on these 2nd-and-longs was lowest against the Rams defense out of any team. It’s just dubious to think this pattern holds up on a defense with lesser talent. Moreover, on 3rd-and-short (a down-and-distance in which the dominant strategy is running the ball), the Rams ranked in the bottom half of opponent passing percentage and gave up the 2nd highest success rate on run plays.

Another flaw in relying on FiveThirtyEight’s DBOE metric too heavily is that certain downs-and-distances call for different dominant strategies by the offense. The behavior of opposing offenses in these distinct situations is where Robert Saleh emerges as a superior candidate. The 49ers defense faced the 9th-highest percentage of run plays on 2nd-and-longs in 2020. They also tied for the second-lowest success rate on passing plays in these situations. This pattern holds up across Saleh’s tenure as defensive coordinator, with the 49ers ranking 12th, 4th, and 1st in run-play percentage on 2nd-and-longs in the three seasons prior to 2020. Since 2018, the 49ers defense allowed a below-average success rate and yards per attempt on 2nd-and-long passing plays each year.

The offense’s woes on 2nd-and-long contributes to the stinginess of the 49ers pass defense on third down. They are tied for 4th in lowest success rate on all third-down passes in 2020, after earning the 2nd-lowest success rate in 2019. Even though success rates were above league-average in 2017 and 2018, the 49ers defense still allowed below-average yards per attempt on third-down passes those seasons too. I can’t prove that Saleh has a particular box count tendency on 2nd-and-long which is responsible for this pattern, but the numbers suggest there’s something structural he’s doing right each year.

Saleh’s tendency for above-expected box count (for all plays, as reported in FiveThirtyEight) is most beneficial on 3rd-and-short when the dominant strategy is to run the ball. The 49ers allowed a below-average success rate on 3rd-and-short runs each of the last three seasons, and a below-average yards per attempt in all four of Saleh’s seasons with them. There is far more to coaching than getting the analytics right. But doing so is a sign that Saleh is instinctively aware of what tactics offense can use to pick up advantages at the margins. These are the indicators of sustained success I want to see when I am considering a defensive coach for a head coaching job.

Frustratingly, analytics don’t show a lot of stable trends in performance of different defensive play-calls. It’s even more true for defense than offense that talent and execution trump all else. Saleh comes from the Pete Carroll coaching tree which ranks among the best at cultivating both of those qualities. The X’s and O’s were not particularly complex for the Legion of Boom and they aren’t for his 49ers defenses either. Like those Seahawk teams, the 49ers primarily use single-high coverages (Cover 1 and Cover 3); they did so on 60% of snaps in the 2019 season, according to USA Today. The arrival of Richard Sherman helped lock down one-third of the field, as he did in Seattle. The 49ers did use more two-high coverages, namely Cover 4, against teams with potent deep passing games like the Kansas City Chiefs in the Super Bowl. The defensive line has been loaded with talent (DeForest Buckner, Nick Bosa, and Arik Armstead just to name a few), allowing the 49ers to lean on a four-man pass rush in a standard 4-3 front.

By all accounts, Saleh seems like an impressive young coach who is worthy of consideration. The fact that Kyle Shanahan, one of the top offensive minds (and a frequent user of play-action), chose him out of all available candidates for defensive coordinator is worth something too. I am as guilty as anyone in being biased towards wanting long-term stability on the offensive side of the ball. It reflects the unfortunate reality of the sport that offensive performance is stickier and more predictive of overall team performance year-to-year.

With that said, there are certain areas essential to offensive performance where Saleh has managed to achieve impressive consistency on his defensive units. I can be convinced he knows what to look for when choosing his offensive coordinator and quarterback. If I were to strike out on my top two choices, I’d take the leap for Saleh.

The widest disparity between media consensus and my own opinion seems to be for Arthur Smith whom I worry will struggle to replicate his formula with the Titans on another team

Arthur Smith’s Resume: Tennessee Titans (Offensive Coordinator, 2019-Present), Tennessee Titans (Quality Control Coach/Offensive Line & TEs Assistant/Assistant TEs Coach/Tight Ends Coach, 2011-2018), University of Mississippi (Defensive Intern & Administrative Assistant, 2010), Washington Redskins (Defensive Quality Assistant, 2007-2008), University of North Carolina (Graduate Assistant, 2006)

In many ways, Smith does fit the criteria for my ideal head coach candidate. He has overseen an offense that ranked in the top ten for explosive plays and ranked first in percentage of pass attempts with play-action. The starting quarterback, Ryan Tannehill, has drastically improved his production compared to earlier in his career. The offensive line has performed admirably well, even after losing one of the key starters (right tackle Jack Conklin) the previous offseason. What’s not to like?

I’ll start by posing this question: what if Smith didn’t really turn Tannehill’s career around? With the misfortune of playing under Adam Gase in Miami (h/t @benbbaldwin), Tannehill had the worst average passing EPA out of 32 qualifying quarterbacks in 2016-2018, but also had the 8th-highest completion percentage over expectation (CPOE). This weird combination suggests Gase is a uniquely horrible coach who squandered the value his quarterback added to the passing game. Kudos to Smith for being not as abysmal as Gase, but the bar for a head coaching candidate should be higher than that.

The play-action component matters a lot too. Smith deserves credit for recognizing its high value, but it’s crucial to recognize that quarterback performance on play-action (h/t Steven Ruiz) is volatile year-to-year. In other words, play-action usage speaks to Smith’s strengths as a play-designer, but not as a quarterback developer. Dropback attempts that don’t involve play-action, on the other hand, are more consistent year-to-year. Sure enough, Tannehill ranked fourth in December 2019 for yards per attempt on these throws, and he now ranks fourth in average EPA on these throws for the 2020 season. Perhaps Tannehill’s production on non-play action passes is where Smith’s influence gets captured.

But it’s curious that only Tannehill clicked with Smith and Marcus Mariota did not (resulting in his benching after Week 6 last season). The sticking point for me is the drastically different results of the celebrated Titans run game between Mariota’s starts and Tannehill’s last season. According to @BufBillsStats, Derrick Henry had a bottom 4 expected yards at handoff among AFC teams and an actual 3.7 yards per rush in Mariota’s 6 starts. With Tannehill at quarterback the next 6 starts, Henry was in the top 10 for expected yards at handoff and had actual 6.1 yards per rush.

This would not be a big deal if Smith shared Daboll and Bieniemy’s tendencies in favoring the pass on early downs and leaning on the run game situationally. If Smith really did bring out the best in Tannehill and actually exploited that improvement when it is most advantageous to do so, more power to him. He clearly does not. The Titans ranked 3rd in rushing percentage on 1st-and-10 in 2019 and 1st in 2020. They also ranked in the top 10 for rushing percentage both seasons on 2nd-and-long; worse yet, the Titans’ rushing success rate was either at or below league-average in those situations.

Sure, I get that Henry is a thrill to watch run with the football. There are statistics for running backs which are stable year-to-year—yards after contact and rushing yards over expectation are two of them—and Henry ranks among the elite at these. This doesn’t change the fact that, before Tannehill became the quarterback of Smith’s offense, Henry’s yards per rush was tied with the likes of Sony Michel and David Montgomery. In fact, the Titans’ yards per rush on 1st-and-10 in those games was below league-average.

This is a long-winded way of saying I’m skeptical that Smith’s early down tendencies will be sustainable for another team. It is a concern I would have even if Smith manages to find another running back as elite as Henry. The even more worrying tendency in Smith’s play-calling is that, when the dominant strategy is to run the ball, he doesn’t pound the rock enough! This season, the Titans threw the ball on 56% of 3rd-and-short (1 to 3 yards to go) plays in one-score games, a rate that was 11th in the league. The Titans also ranked 2nd in passing percentage on 3rd-and-medium (4 to 7 yards to go) this season and 10th in 2019. If the Titans rushing attack were as uniquely awesome as it’s often claimed to be, surely Smith ought to be leaning on it for at least the same clip as the Baltimore Ravens (1st in rushing percentage on 3rd-and-short and 3rd-and-medium each of the last two years). When it comes to 3rd downs: Let. Derrick. Cook.

The Ravens example is particularly helpful because it illustrates the dependency of a run-dominant offense on the quarterback’s performance—both on the ground and the air. It’s entirely possible Smith succeeds in his first acquisition of a new starting quarterback when he becomes a head coach, rendering my concerns moot. Perhaps he lands with a team that already has an established starting quarterback (think DeShaun Watson and the Houston Texans). In any case, the information we have available to us suggests that Smith’s play-calling tendencies leave an offense at a disadvantage on the margins.

The one exception, heavy use of play-action, should not be dismissed lightly. The X’s and O’s which marry the Outside Zone-centric run game with deep over and intermediate crossing routes by electric weapons like A.J. Brown and Corey Davis are sound. It’s the formula the 49ers, Rams, Packers, and Browns have used as well. The difference I foresee with Smith and the play-callers of those teams is that Smith coaches his offense like they’re the Ravens on 1st-and-10, and then gets gun-shy on the ground when he just needs a few yards.

Moreover, the lack of any correlation between rushing metrics—number of rushes, rushing percentage, and rushing success rate—with play-action yards per play has been well-documented by Ben Baldwin. USA Today’s Travis Sommers found a weak correlation coefficient between a team’s rushing EPA and play-action pass EPA (11%), but a much stronger one for play-action pass EPA’s relationship with non-play action pass EPA (34%) and PFF passing grade (49%). An instructive example in Baldwin’s piece, the Denver Broncos saw a jump in play-action yards per dropback between 2011 and 2012 from 7.0 to 10.5, despite a 7% drop in rushing percentage from its league-high 49% in 2011.

The lurking variable here is that the Broncos switched from Tim Tebow to Peyton Manning as their starting quarterback. But that’s the point I’m trying to make: the Titans’ play-action efficiency is largely the product of Tannehill being excellent at quarterback, not Smith calling so many run plays on early downs. To the extent that the run game correlates with play-action production, it’s in how well the offensive line run-blocks, not how many run plays are called. Steven Ruiz found that the R-squared between adjusted line yards and play-action success rate is a fairly high number: 25%. For those not well-versed in statistics, a high R-squared means that the movement of one variable is explained by movement in the other. The Titans ranked fourth in adjusted line yards last season, meaning that the offensive line is uniquely good at driving run defenders off the line of scrimmage. The eye test for Conklin (now with the Cleveland Browns), left tackle Taylor Lewan, and left guard Rodger Saffold especially backs this up. The link here is that good run-blocking offensive lines are also good at selling the run with their blocking techniques on play-action.

To make the leap in assuming that Smith’s formula in Tennessee will work for another team, it requires the belief he will have another above-average talent at quarterback and another elite offensive line. That may sound a little too obvious at first (one might say, “all coaches need good quarterbacks and offensive linemen”). But my point here is that Smith is unlikely to be a head coach who can mask the shortcomings of his personnel. He will probably be totally dependent on the talent he has at his disposal.

Conclusion

As important as it is to know what qualities to look for in a head coach candidate, it’s equally important to know what qualities should raise concerns. My evaluation of Smith is an example of when I would go against the grain and let someone else take a gamble I don’t believe is worthwhile. Let the chips fall where they will. I believe in the process I’ve laid out in evaluating head coach candidates. I’ll get some evaluations wrong (perhaps some in this very post), but modern NFL trends suggest I’ve outlined a process that increases the odds of an NFL team making a successful hire. The limitations of human judgment and randomness make that the best we can strive to do.