No college team in FBS passes the ball more than Mike Leach’s teams—whether it was Texas Tech, Washington State, or now Mississippi State. This is why it’s surprising when Leach says that, if he didn’t run his Air Raid scheme, the offense he’d want to use is the ultra-run-heavy Wishbone scheme that the likes of Emory Bellard, Barry Switzer, Bear Bryant, and Lou Holtz operated. Along with their overwhelming bias to the run over the pass, Wishbone teams used a crowded backfield with a fullback and two halfbacks aligned behind the quarterback. Leach’s version of the Air Raid uses a heavy dose of four receiver sets.

It’s true that Leach has a reputation for saying weird things pertaining to the likes of Bigfoot and aliens. In this case, he has a cogent explanation and it’s one that upends conventional wisdom on ‘balance’ in football. “To me,” Mike Leach said to X&O Labs, “the ultimate offenses in terms of distribution are what we do and the old school wishbone offense and both of them have wide splits with their lineman.”

Leach generally uses three feet splits between linemen, but sometimes widens them to as large as six feet. This is much larger than the typical one-foot or six-inch splits found in most pro or college offenses today. Wide line splits are like vinyl Jimi Hendrix albums or an antique Cadillac El Dorado of football. They are a throwback to that same era with the Wishbone and plenty of other old systems like the Split-Back Veer, Wing-T, I-Option, and Run-and-Shoot.

The Wishbone offense used these wide line splits to structure an option-based run game. It was the offense du jour of the 1970s and early 1980s with Barry Switzer (Oklahoma), Bear Bryant (Alabama), and Darrell Royal (Texas) all achieving impressive efficiency. The Triple Option (shown above) is its most well-known concept, sometimes invoked as a synonym for the offense. There were complementary traps, counters, and play-action passes, making it a difficult offense to defend. It wasn’t easy to determine who even had the ball. “The wishbone, which I think is a great offense,” Leach said. “There’s nothing 50 percent run about the wishbone. They’re like 95 percent run… But everybody touched the ball. That’s why it’s one of the greatest offenses devised.”

This is the linkage between the Wishbone and the Air Raid offenses. While the former is run-heavy as any offense and the latter is as pass-heavy, they both make the defense account for every offensive skill player. They both also have tactics for attacking the full width of the field—A-gap, B-gap, C-gap, and perimeter alike. The wide line splits in both offenses offer the possibility that attacking the middle of the defense isn’t just a hopeless “three yards and a cloud of dust” endeavor. Instead, there is spacing for a run game that can average up to 6.5(!) yards per play as the 1987 Oklahoma Wishbone offense did, or a pass game that slices defenses with shallow crossers 7-8 yards at a time as Leach’s often does. The pure Wishbone may be extinct in FBS college football, but the Air Raid is a close descendant that still lives.

How the Air Raid and Triple Option are similar

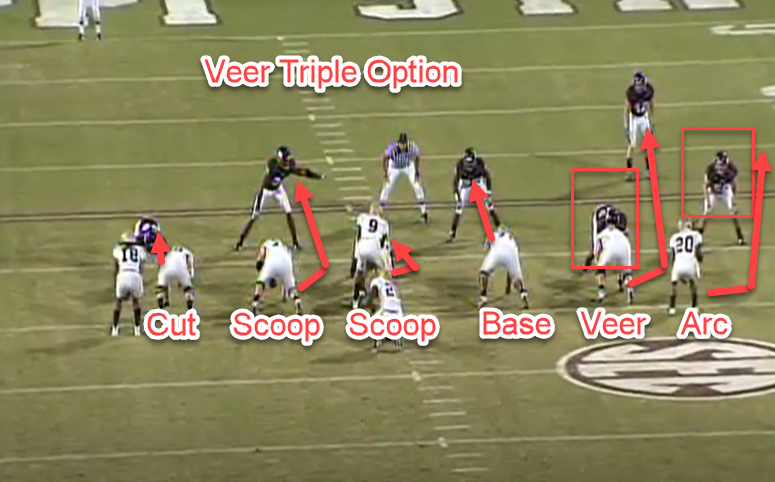

There is another descendant to the Wishbone teams that still live today: the military academy teams which major in the triple option. These “Flexbone” offenses—similar in formation to the Wishbone, but with the two halfbacks moved to the line of scrimmage so they can be more potent receiving threats—use wide line splits to execute veer-blocking for the triple option (hence the name, “Veer Triple”) and its change-ups. After being hired away from the Naval Academy, Paul Johnson had continued using the Flexbone at Georgia Tech and won the ACC Coastal Division 4 times in 11 seasons. Despite Johnson’s success, Power 5 schools are reluctant to embrace the triple option.

A major reason why the military academies in particular still lean on Veer Triple is that cadets have weight restrictions; Air Force head coach Troy Calhoun said that his offensive linemen usually average 255 pounds. In short, Veer Triple is a size-equalizer. The play-design angles the front-side tackle away from the defensive end, so he can veer release to block a smaller player at the second level. The playside guard generally blocks down on a three-technique or linebacker opposite the veer release. The center and backside guard often scoop to double-team a nose tackle until one of them peels off to the backside linebacker.

The key block for Veer Triple is arguably the one by the backside tackle on the defensive end. This block involves a technique called cut-blocking. Cut-blocking is when an offensive player knocks a defensive player down by hitting his knees from the front (a tactic which is legal within five yards of the line of scrimmage). Flexbone offensive linemen are almost always in a three-point or a four-point stance (meaning one or two hands in the ground, respectively) because the offense is so run-centric. Lower stances make it easier to cut-block and to gain body leverage when there’s a size mismatch.

The idea behind the wide line splits is to challenge either defensive end: both the front-side end who is being read by the quarterback and the back-side end who is being held up by the cut-block. Defensive ends are typically the best athletes on the field and the biggest threats to cause a tackle for loss. Widening both ends’ alignments gives the quarterback just enough time to either hand the ball off or roll out of the tackle box to read the pitch defender.

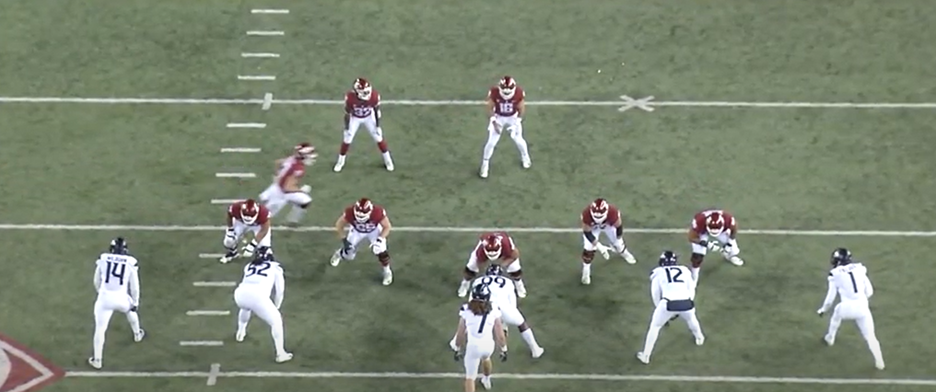

Meanwhile, Air Raid linemen are almost always relatively upright in a two-point stance (no hands in the dirt) because this is advantageous for pass protection. Their assignment is to drop straight back out of their stance into a technique called a vertical set. The idea of widening the angle defensive ends must take to pressure the quarterback mirrors how the Flexbone exploits spacing with veer and cut-blocking.

“The big gaps between the linemen made the quarterback seem more vulnerable,” the great author Michael Lewis wrote in a New York Times article about Leach’s Texas Tech offense in 2005. “Some defenders could seemingly run right between the blockers — but he wasn’t. Stretching out the offensive line stretched out the defensive line too, forcing the most ferocious pass rushers several yards farther from the quarterback. It also opened up wide passing lanes through which even a short quarterback could see the whole field clearly.”

Leach’s offenses have a historically low sack allowed percentage. In five of his last seven seasons at Texas Tech, the Red Raiders ranked 12th or better. They even ranked 1st in 2008. It took time to replicate this success at Washington State, but Cougars eventually ranked 1st in 2018 and 4th in 2019. There may be a similar lag for Mississippi State which ranked a more pedestrian 50th in 2020.

Stunts and blitzes which involve gap exchanges were mostly futile against the Red Raiders and Cougars’ wide line splits because they took more time to execute. Defenses were forced into more vanilla game-plans. Excuse the cliché, but playing defense against an Air Raid offensive line in the most literal sense boils down to winning one-on-one matchups. That’s just how Leach likes it, according to Chris B. Brown:

At one time or another, Leach coached every position on offense, including offensive line. And he had strong views of how line should be played, and both he and [Hal Mumme, the head coach at Iowa Wesleyan, Valdosta State, and Kentucky when Leach was the offensive coordinator at those schools] firmly believed in the value of one-on-one battles. While slide pass protection and zone blocking have increasingly become the rage, Leach always focused on “man blocking,” where the goal was to win the battle versus the guy across from you. The wide splits were simply that principle taken to its extreme: each lineman split out enough to where he was essentially on an island, as far from the quarterback as possible. On the line, at least, the goal was actually to have as many one-on-one matchups as possible. And Leach was confident his guys would win them.

A unique benefit to Air Raid quarterbacks from this pass protection scheme is the wide passing lanes in the middle of the field. Not coincidentally, the Air Raid features a relentless bombardment of shallow crossers. The example above shows the Mesh concept—two shallow crossers from opposite sides intersecting about 5 yards downfield. The defense had a decent zone coverage to avoid the natural rub that the crossers typically create against man. However, the offensive line’s stellar pass protection buys quarterback Gardner Minshew time to find the receiver on the sit route (Mesh’s built-in zone-beater) behind the crossers. The huge throwing lane in the A-gap is key to the ease of this throw. You don’t have to squint to see the parallels with how a triple option team manufactures space. All you need to see is the three feet of grass between the center and right guard’s feet.

The Air Raid’s main counter-punch is the screen game and it incorporates cut-blocking too

When defenses overplay the threat of the Air Raid’s bread-and-butter crossing routes, Leach leans on his screen and quick game. (And, as Groucho Marx would say, “the opposite is also true.”) According to Derrik Klassen, Leach’s last two Washington State quarterbacks, Gardner Minshew (2018) and Anthony Gordon (2019), threw the ball at or behind the line of scrimmage on 28% and 22% of attempts respectively. For perspective, those throws comprised less than 16% of attempts by Kyler Murray, Daniel Jones, and Drew Lock in their final college seasons.

This pattern hasn’t changed since Leach arrived in Mississippi State. According to SEC Statcat, screens were Leach’s third-most common designed passing play last season, after Mesh and Four Verticals. Mississippi State went 4-7, but screens were a bright spot for them among SEC competition. The Bulldogs ran more screens than any other SEC team (49), and also had the second-highest success rate (47%) on them. Their success rate trailed only Ole Miss (50%) who ran just 14 screens. PFF writer Seth Galina found that this efficiency at screens extended back to Washington State too:

Leach, however, makes up for his lack of a designed run game with screen passes. In 2019, Washington State finished fifth in the country in total number of screen passes, and they finished second in that regard in 2017. They were also quite good at running them, too, as they finished 2019 as the fifth-best screen team in terms of expected points added (EPA) per play at 0.252, while their 0.139 EPA per screen play over the last three seasons ranks sixth over that span.

Generally, Leach’s screen plays are run for receivers. In fact, 236 of the 324 screens over the past three seasons went to players lined up wide or in the slot. However, in 2017, Leach threw 40 of his 116 screens to players lined up in the backfield, so he is more than capable of adapting.

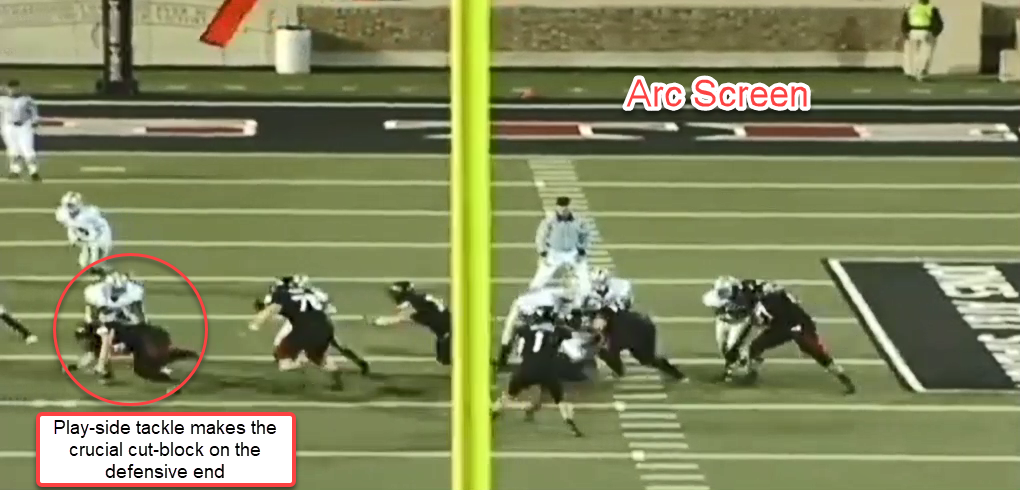

In my opinion, Leach’s consistent success in the screen game is another product of the Wishbone’s influence on him. In the fast-moving Arc screen, the wide line splits make all of the defensive linemen besides the play-side defensive end cover more ground to get to the screen. Unlike the Veer Triple, it’s the play-side tackle who makes the most important cut-block on this play, not the back-side tackle. This is because the play-side defensive end is the most immediate threat to disrupt the screen. The end is put into a similar bind as he would be on Veer Triple; his instinct is to crash down and rush the quarterback, but the presence of a screen man (in place of the pitch man) neutralizes that threat. The back-side linemen attempt cut-blocks as well for good measure.

The main Air Raid tunnel/jailbreak screen (“Lisa” for left, “Rita” for right) is designed to target linebackers and box safeties. Both tackles drop into vertical sets, while the play-side guard cuts the first defender outside the box. This play works because defenses won’t do gap exchanges against wide line splits. Because the tackle lures the defensive end up field, the guard should have a free release and clean angle to his man. Another of Leach’s tunnel screens (“Larry” for left, “Randy” to right) slips the play-side tackle past the defensive end, so he can block the flat defender who is usually a cornerback or an outside linebacker. The slightly shorter distance for the cut blocker afforded by the wider line splits is a subtle difference that goes a long way on these slow screens.

The Air Raid has a surprisingly efficient run game of its own

Leach seldom calls any run play. Despite the consistent efficiency of designed quarterback runs, he’s never involved the quarterback as a serious run threat. Teams that use the read option do so to gain a +1 advantage in the box, with the quarterback “blocking” a defender with his read. Instead, Leach typically instructs his quarterback to only check into a run if the box count is 5 or less. This means the offensive line accounts for all defenders and the read option is not needed, per his logic.

This allergy to running the ball against boxes with 6+ men does boost the average efficiency of run plays. In fact, the 2019 Washington State offense produced the highest success rate (67%) by a wide margin to RB rush attempts; the lead here was bigger than the one between second-ranked Nebraska (53%) and seventeenth-ranked Louisville (40%). This carried over in 2020. Despite Mississippi State’s issues, they actually ranked 4th in success rate to RB rush attempts.

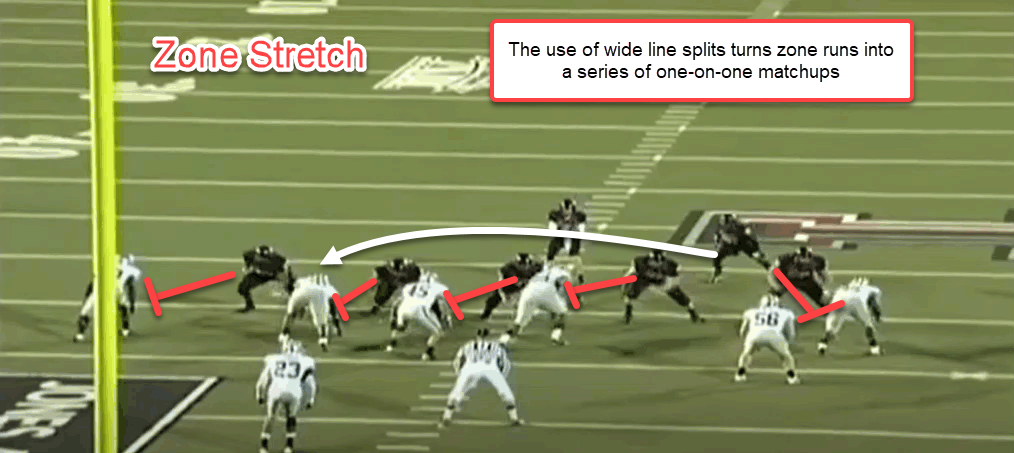

Zone-blocking is the most common scheme in Leach’s offense by a huge margin (71% of run plays in 2019, according to Seth Galina). The wide line splits make their version of zone-blocking function as a series of one-on-one blocks which mirror the man-blocking principles in Air Raid pass protection. This is a noticeable difference from how most offenses execute the scheme. It’s typically blocked as a series of double-teams in which one lineman peels off to the second level.

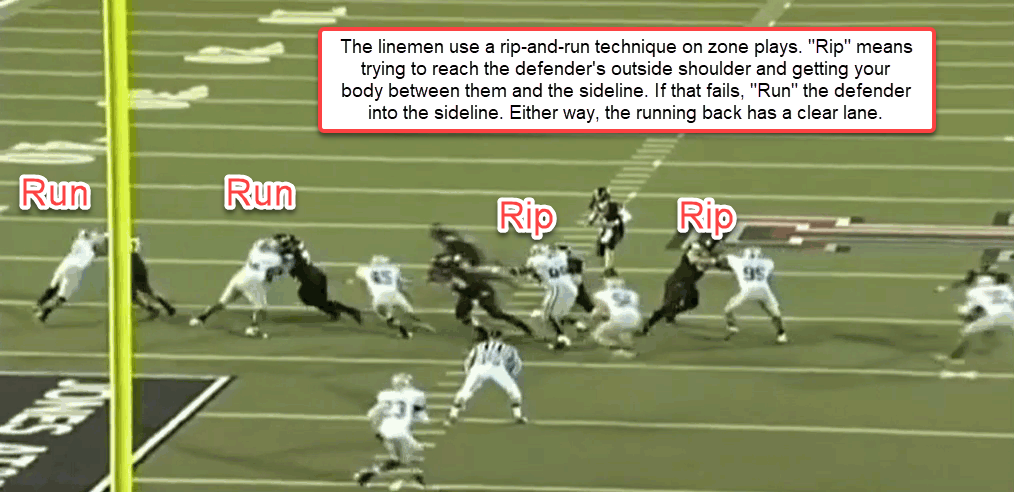

Here, the offensive linemen are assigned to use a “rip-and-run” technique. This means that they either reach the defender’s outside shoulder and block him from the sideline (“rip”), or, if that fails, transition to driving that defender into the sideline (“run”). That’s a fairly normal method of doing zone-blocking. The unique advantage of Leach’s approach is the abundance of space that can open in the A or B gaps when they would be congested in an offense with tight line splits.

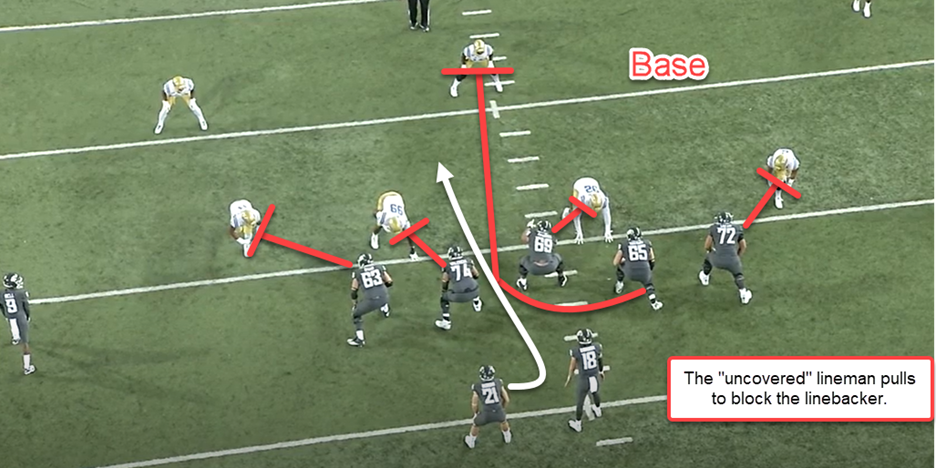

The second-most frequent run scheme, “Base”, features a fold block where a pulling lineman blocks the middle linebacker and the other blockers all down-block the remaining defensive linemen. The assignments are basically the same as Leach’s man pass protection scheme. Base works great against even fronts because both offensive tackles have great angles against defensive ends who are expecting to face a deep vertical set. The middle linebacker is also vulnerable to the fold block because the alignment of the running back signals a zone run to the opposite side as this play (when facing an offense in shotgun, defenses are generally coached to expect the play to be the opposite side of the running back).

There is one problem that comes with Leach’s approach of letting the defense dictates when to run the ball. Defenses are increasingly dropping 8 into coverage against his teams, and the low volume of efficient run plays is not enough to make defenses pay. Galina found that, in 2017-2019, Washington State’s EPA/play against 4+ rushers was +0.15. It was -0.06 EPA/play against 3 or less. Curiously, Pac-12 defenses only rushed 3 or less 33% of snaps. In Leach’s first four games at Mississippi State though, SEC defenses had rushed 3 or less on 63% of snaps. That figure is 83% of snaps if the LSU game in which the Bulldogs earned +0.32 EPA/play is removed. In the 3 games afterward, they earned an astonishingly bad -0.44 EPA/play.

Another problem is that there are times when running the ball is the dominant strategy like 3rd-and-short. Defenses are fully aware of this. Mississippi State had the 2nd-lowest run percentage on 3rd-and-short plays in 2020 which contributed to its 5th-lowest success rate on those plays. This issue plagued Leach’s more successful Washington State offenses too. The Cougars ranked dead-last in run percentage on 3rd-and-short in 2019 and had the 13th-lowest success rate on those plays.

At risk of sounding like a degenerate sports radio show caller, one solution is obvious: run the ball more. There may be a way to lure defenses out of using eight-man coverages without running the ball, but Leach hasn’t found it yet. If box count is the concern, then he could integrate the quarterback as a run threat. This is something that the Wishbone teams that Leach reveres certainly understood. Don’t get me wrong: Leach is a breath of fresh air to football discourse when he says, “if you’re establishing the run on an 8 man box, you ain’t establishing shit.” But there is a middle ground to be had here when facing 6 or even 7 man boxes.

Final Thought: Leach thinks the original pure Wishbone could be run in the NFL. It’s not that crazy of an idea.

At Washington State, Leach co-taught a seminar on football strategy and insurgency warfare in the 2019 spring semester. Due to popular demand, the class had an audition consisting of an essay to be answered by all students who applied. The prompt: “Is the wishbone a potentially viable offense for the NFL?”

Leach didn’t penalize a “yes” or “no” answer per se, but he did take a side himself:

“I think it would work in the NFL,” he said recently in Pullman. “I think it would be very difficult for teams to prepare for a triple-option team. I do think you go through some quarterbacks, and you’d have to make sure your quarterbacks can run. However, you can get some great options quarterbacks because there’s not a big value on them in regard to the NFL. You’d definitely have the pick of guys that would have that skill set, and honestly it wouldn’t be very expensive to draft them — if you even had to draft them.”

The value of quarterbacks in the run game has proven to be resilient at the NFL level, as Sharp’s research suggests. Leach’s teams also provide evidence that wide line splits—the same ones used by the Wishbone offenses—make rushes by the running back more efficient. It isn’t necessary to spread the field the way the Air Raid does for this; Flexbone teams show that the threat of the triple option can yield run plays with positive average EPA. Leaning on the run game is also the dominant strategy in high-leverage situations like the low red zone (10 yards to goal or less) and 3rd or 4th-and-short. The way NFL teams run the ball now is mostly equivalent to running into a brick wall, but it doesn’t have to be that way. A fun thought experiment is to imagine how efficient Derrick Henry, Nick Chubb, Aaron Jones, or Saquon Barkley would be if they actually had room to run between the tackles.

The strongest advantage the pure Wishbone holds over the Air Raid ironically comes in its passing game—namely, play-action. This is a tool that Leach has failed to exploit adequately. Leach’s last two quarterbacks at Washington State used an extraordinarily low percentage of play-action on passing attempts. Klassen’s data says that Gordon used a play-fake on just 12% of his attempts, while Minshew used it on 22%. This is behind the last two years’ early round prospects: Kyler Murray (49%), Tua Tagovailoa (46%), Drew Lock (46%), Jalen Hurts (42%), Justin Herbert (37%), Daniel Jones (30%), Dwayne Haskins (26%), and Joe Burrow (26%). Intuitively, if you only will run the ball when there are five defenders or less, you’re only selling the play-action when the defense is best-positioned to defend the pass.

It’s true there’s no evidence that play-action efficiency is correlated with a team’s run game efficiency. Still, it doesn’t hurt that the Wishbone formation is optimal for both facets. If play-action works best with the maximum number of blockers, a three-back formation seems to be ideal. In addition to plenty of play-fakes setting up two-man routes for the receivers, the 1980s Oklahoma playbook also featured wheel routes, seam routes, and even a crosser to the backs. We know from Sharp’s research that a running back alignment is the superior one to execute a wheel route, and that running back seam routes are efficient. No other offense would make the defense fear the run more and also leave itself more vulnerable to the corner 3 of the NFL than the Wishbone. Simply put, I’m with Leach. The Air Raid—a system which bucks conventional wisdom on run-pass balance—boosts the quixotic case for a Wishbone renaissance.